Study Helps Researchers Better Understand Brain Protein’s Role In Down Syndrome And Alzheimer’s Disease

Findings of a new study from the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Waisman Center investigating the link between a protein typically associated with Alzheimer’s disease, are revealing more information about the earliest stages of the neurodegenerative disease and that this protein’s impact on memory and cognition may not be as clear as once thought.

Alzheimer’s disease is the sixth leading cause of death in the U.S. People with Down syndrome are born with an extra copy of the 21st chromosome, where the gene that codes for the amyloid- protein that leads to the development of plaques in the brain, a hallmark characteristic of Alzheimers disease, resides.

According to the Alzheimer’s Society of Canada (ASC), the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease in people with Down syndrome is about three to five times greater than the general population. As with Alzheimers disease, the risk increases with age. Since  people with Down syndrome have an additional copy of the 21st chromosome, they are prone to an over-production of the protein. Not everyone with Down syndrome, however, develops Alzheimers disease.

people with Down syndrome have an additional copy of the 21st chromosome, they are prone to an over-production of the protein. Not everyone with Down syndrome, however, develops Alzheimers disease.

A research team led by Sigan Hartley, UW-Madison assistant professor of human development and family studies, and Brad Christian, a UW-Madison associate professor of medical physics and psychiatry and director of PET Physics in the Waisman Laboratory for Brain Imaging and Behavior looked at the role of the brain protein amyloid-beta peptide (Abeta) in adults  living with Down syndrome, a genetic condition that leaves people more susceptible to developing Alzheimer’s. They published their findings in the September issue of the journal Brain.

living with Down syndrome, a genetic condition that leaves people more susceptible to developing Alzheimer’s. They published their findings in the September issue of the journal Brain.

The research paper, entitled “Cognitive functioning in relation to brain amyloid- in healthy adults with Down syndrome” (Brain (2014) 137 (9): 2556-2563. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu173), is coauthored by Sigan L. Hartley, Marsha R. Mailick, Sterling C. Johnson, and Bradley T. Christian of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Waisman Centre,Madison, Wisconsin; Benjamin L. Handen, Julie C. Price, Annie D. Cohen, William E. Klunk, and Iulia Mihaila of the University of Pittsburgh, Department of Psychiatry, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Darlynne A. Devenny of the New York State Institute for Basic Research in Developmental Disabilities, Albany, New York; and Regina Hardison of the University of Pittsburgh, Epidemiology Data Centre, Pittsburgh.

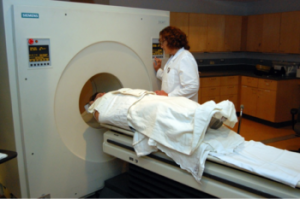

The coauthors note that nearly all adults with Down syndrome show neuropathology of Alzheimer’s disease, including Abeta deposition, by their fifth decade of life. In the current study, which was conducted over the course of two days, researchers used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) scans to capture images of the participants’ brains

The UW-Madison scientists, along with collaborators at the University of Pittsburgh examined the association between brain amyloid- deposition, assessed via in vivo assessments of neocortical Pittsburgh compound B, and scores on an extensive neuropsychological battery of measures of cognitive functioning in 63 adults (31 male, 32 female) with Down syndrome aged 30 – 53 years who did not clinical signs of Alzheimer’s or other forms of dementia. They found that twenty-two of the adults with Down syndrome were identified as having elevated neocortical Pittsburgh compound B retention levels, but showed no evidence of diminished memory or cognitive function when compared to those without elevated levels of the protein. Similarly, when assessed as a continuous measure, amyloid- levels were not tied to differences in memory or cognitive ability, such as changes in visual and verbal memory, attention and language. The coauthors observe that this robust association makes it difficult to discriminate normative age-related decline in cognitive functioning from any potential effects of Abeta deposition.

Moreover, they report that when controlling for chronological age in addition to mental age, there were no significant differences between the adults with Down syndrome who had elevated neocortical Pittsburgh compound B retention levels and those who did not on any of the neuropsychological measures.

The researchers say their findings indicate that many adults with Down syndrome can tolerate Abeta deposition without deleterious effects on cognitive functioning. However, they caution that they may have obscured true effects of Abeta deposition by controlling for chronological age in their analyses. Moreover, the subject sample included adults with Down syndrome who were most resistant to the effects of Abeta deposition, since adults already exhibiting clinical symptoms of dementia symptoms were excluded from the study.

“Our hope is to better understand the role of this protein in memory and cognitive function,” says Dr. Hartley in a release. “With this information we hope to better understand the earliest stages in the development of this disease and gain information to guide prevention and treatment efforts.”

[adrotate group=”3″]

With funding from the National Institute of Aging, the researchers plan to follow these 63 adults for the next several years, to continue to track the accumulation of amyloid- and its effects over time.

However, in the meantime the findings of their study not only may help scientists better understand the condition as it impacts those living with Down syndrome, but are also relevant to adults without the genetic syndrome.

“There are many unanswered questions about at what point amyloid-, together with other brain changes, begins to take a toll on memory and cognition and why certain individuals may be more resistant than others,” says Dr. Hartley.

Drs. Hartley and Christian also partnered with Marsha Mailick, interim vice chancellor for research and graduate education and Vaughan Bascom and Elizabeth M. Boggs Professor, and UW Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) investigators on the study. The focus of Dr. Mailick’s research is on the life course trajectory of developmental disabilities. She is interested in how the behavioral phenotype of specific developmental disabilities, including autism, fragile X syndrome, and Down syndrome, changes during adolescence, adulthood, and old age. In addition, she studies how the family environment affects the development of individuals with disabilities during these stages of life, and reciprocally how parents and siblings of individuals with disabilities are affected. She recently completed an epidemiological study of the premutation of FXS and a 20-year follow up of a cohort of older adults with Down syndrome, examining how the family environment predicts outcomes in midlife and old age. Together, these studies offer specific insights about developmental disabilities across the life course, and the impacts on families.

Drs. Hartley and Christian also partnered with Marsha Mailick, interim vice chancellor for research and graduate education and Vaughan Bascom and Elizabeth M. Boggs Professor, and UW Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) investigators on the study. The focus of Dr. Mailick’s research is on the life course trajectory of developmental disabilities. She is interested in how the behavioral phenotype of specific developmental disabilities, including autism, fragile X syndrome, and Down syndrome, changes during adolescence, adulthood, and old age. In addition, she studies how the family environment affects the development of individuals with disabilities during these stages of life, and reciprocally how parents and siblings of individuals with disabilities are affected. She recently completed an epidemiological study of the premutation of FXS and a 20-year follow up of a cohort of older adults with Down syndrome, examining how the family environment predicts outcomes in midlife and old age. Together, these studies offer specific insights about developmental disabilities across the life course, and the impacts on families.

For more information about Down syndrome and its relation to Alzheimers disease, as well as screening and treatment, you can read the ASC’s information sheet on the topic.

Sources:

University of Wisconsin-Madison Waisman Center

Brain

Alzheimer’s Society of Canada

Image Credits:

University of Wisconsin-Madison Waisman Center