Llama Antibodies May Work to Visualize Brain Changes in Alzheimer’s Patients

Written by |

Antibodies extracted from llamas can visualize amyloid-beta plaque and tau deposits in the brains of live animals — a finding that may lead to a way to track Alzheimer’s disease-related brain changes in people before symptoms appear.

The antibodies were shown to work in mice, but researchers have been unable to visualize their presence in the human brain, and are working to develop a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) system that can be used with the antibodies.

The study, “Camelid single-domain antibodies: A versatile tool for in vivo imaging of extracellular and intracellular brain targets,” appeared in the Journal of Controlled Release.

Detecting changes in the brain of Alzheimer’s patients is important for more than just a correct diagnosis. Many treatments are now being developed to prevent further decline in patients in the earliest disease stages, and physicians need to know as early as possible which patients are in need of interventions.

But the brain is guarded by a layer of cells that is impenetrable to most molecules, making the task of visualizing a certain protein in the brain difficult.

In a large collaboration involving the French research institutions Institut Pasteur, Inserm,CNRS, CEA, and the Pierre & Marie Curie and Paris Descartes universities, as well as the Swiss pharmaceutical giant Roche, researchers turned to llamas for a possible solution.

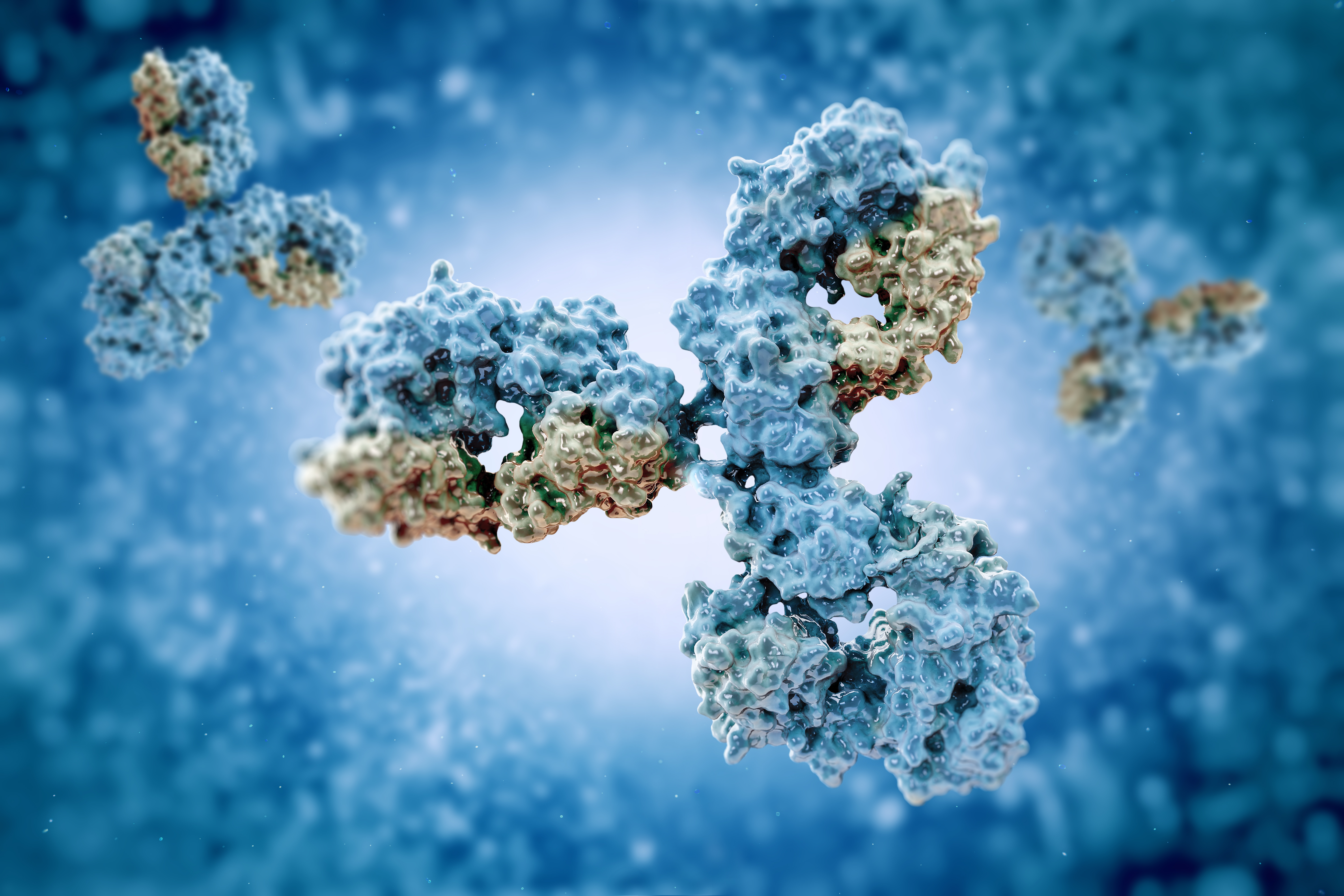

The llama has particularly small antibodies of use in trying to get them across the blood-brain barrier. The team used a part of the llama antibodies to engineer two new types, which were able to bind to both amyloid-beta plaque and neurofibrillary tangles, consisting of aggregated tau inside neurons.

The antibodies were also labeled with fluorescent dyes, allowing scientists to see where they bind when using a fluorescent microscope.

Lab tests, using brain tissue from deceased people with Alzheimer’s disease, confirmed that the new antibodies found their target. And when researchers injected them into two mouse models of Alzheimer’s — each having either amyloid plaque or tau deposits — they showed found their way into the brain, and lit up in the regions of Alzheimer’s brain changes.

“Being able to diagnose Alzheimer’s at an early stage could enable us to test treatments before the emergence of symptoms, something we were previously unable to do,” Pierre Lafaye, at the Institut Pasteur and the study’s senior author, said in a press release.

He also noted that the antibodies could be used in combination with drugs, allowing them to be delivered in a more precise manner to the place they are most needed.