Discovery of Human Brain Lymph Vessels Offers Alzheimer’s Researchers New Possibilities

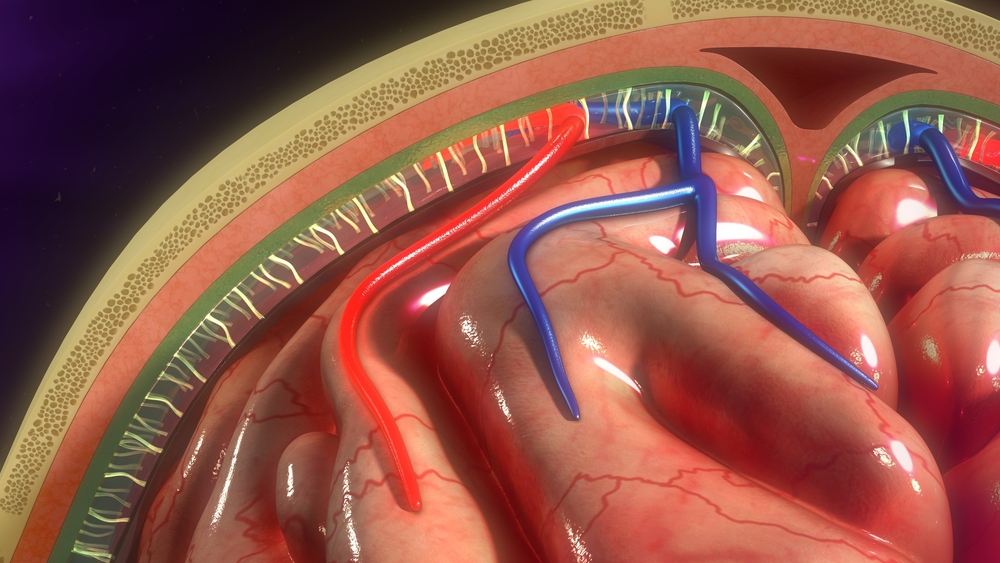

In a discovery that might provide an entirely new angle to Alzheimer’s disease research, scientists have mapped lymphatic vessels to the outside of the brains of living humans.

Because these vessels are the main route traveled by immune cells, the finding, described in the journal eLife, may allow scientists to study if, and how, immune processes are involved in the neurodegenerative condition. But lymphatic vessels also are used for removing waste, a process that may have implications for Alzheimer’s.

Until a few years ago, it was a generally accepted notion that the brain lacked lymphatic vessels. In fact, the brain was long considered “immune-privileged,” meaning that immune processes did not take place there as they did in the rest of the body.

But in 2015, two independent research groups reported that lymph vessels, indeed, were present in the membranes surrounding the brain in rodents.

The study, “Human and nonhuman primate meninges harbor lymphatic vessels that can be visualized noninvasively by MRI,” took this knowledge one step further, showing that these vessels also exist in monkeys and humans.

They also described imaging methods, commonly used for other purposes, which could allow researchers to study the vessels in living people.

To visualize the vessels, the team at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) at the National Institutes of Health used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) together with different dyes.

One of these dyes could leak out from blood vessels in a brain membrane called the dura. The dye molecules are, however, too small to leak from blood vessels inside the brain, which are equipped with a tighter barrier.

In combination with a specific type of imaging, this type of dye usually makes blood light up. But when scientists tuned the scanner so that blood vessels were not as prominent, other vessels appeared, and they seemed to have taken up some of the injected dye.

The observation made researchers suspect that they had found lymph vessels, but to confirm this they injected the volunteers with a dye that did not leak. When using this dye, the second type of vessel did not light up.

“We literally watched people’s brains drain fluid into these vessels,” Daniel S. Reich, MD, PhD, a senior NINDS investigator and the study’s senior author, said in a press release.

“We hope that our results provide new insights to a variety of neurological disorders,” added Reich, who was, in fact, inspired to conduct the study when he heard of the earlier findings in rodents.

“These results could fundamentally change the way we think about how the brain and immune system interrelate,” said Walter J. Koroshetz, MD, director of NINDS.

The discovery also suggests that lymph nodes may be used to drain fluid from the brain in the same way they do in other organs.

“For years we knew how fluid entered the brain. Now we may finally see that, like other organs in the body, brain fluid can drain out through the lymphatic system,” Reich said.

And with this comes the possibility that the vessels are used to transport waste out of the brain.

“The discovery of a lymphatic system in the brain raises the possibility that a disorder of the lymphatic system is somehow involved in the causation of Alzheimer’s disease,” Michael Weiner, MD, a professor of radiology at the University of California San Francisco, who was not involved with the study, told NPR’s Jon Hamilton in an article on the findings.

At the moment, however, the team does not know what types of substances are transported in these vessels or how the process works.

Finding out might provide entirely new insights into neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease.