Maintaining Active Brain May Slow Cognitive Decline in Neurodegenerative Disorders, Study Shows

Written by |

An intellectually active lifestyle may help protect against neurodegeneration, delaying symptoms and loss of the brain’s gray matter, which is essential for motor control and sensory perception, a study shows.

The study, “An active cognitive lifestyle as a potential neuroprotective factor in Huntington’s disease,” was published in the journal Neuropsychologia.

Studies on aging and dementia suggest that a cognitive stimulating lifestyle may help halt cognitive decline that characterizes multiple neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s or Huntington’s diseases.

Previous studies on Alzheimer’s disease reported that patients with higher levels of education kept their cognitive functions intact despite the severity of the disease. This indicates that cognitive engagement — the level of cognitive activity throughout life — does not provide protection from neurodegeneration, but “rather from the cognitive symptoms that result from this degeneration, conferring resilience but not resistance,” the researchers wrote.

However, in individuals at risk of Alzheimer’s disease, higher levels of engagement in intellectually stimulating activities have been associated with better cognitive performance as well as greater gray matter volume in areas of the brain that are more vulnerable in Alzheimer’s. Gray matter refers to areas of the central nervous system (brain, brainstem, and cerebellum) made up of neuron cell bodies. This suggests that cognitive engagement may in fact provide some sort of protective effect against neurodegneration.

Huntington’s disease is a neurodegenerative genetic disorder caused by an abnormal expansion of three nucleotides (the building blocks of our DNA), called CAG, in the Huntingtin (HTT) gene. The disease shares several features with Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease — delayed onset, neuron loss, and accumulation of toxic protein aggregates.

Researchers at the Bellvitge Biomedical Research Institute and the University of Barcelona in Spain used Huntington’s disease as a model to study the effects of cognitive engagement on neurodegenerative processes from its early stages.

They evaluated 32 Huntington’s gene carriers at different stages of the disease — 21 manifesting the disease and 11 diagnosed as premanifest — along with 30 controls matched for age and years of education.

Patients were evaluated for motor and behavioral parameters, as well as cognitive performance using the Cognitive Reserve Questionnaire, a test that measures cognitive engagement.

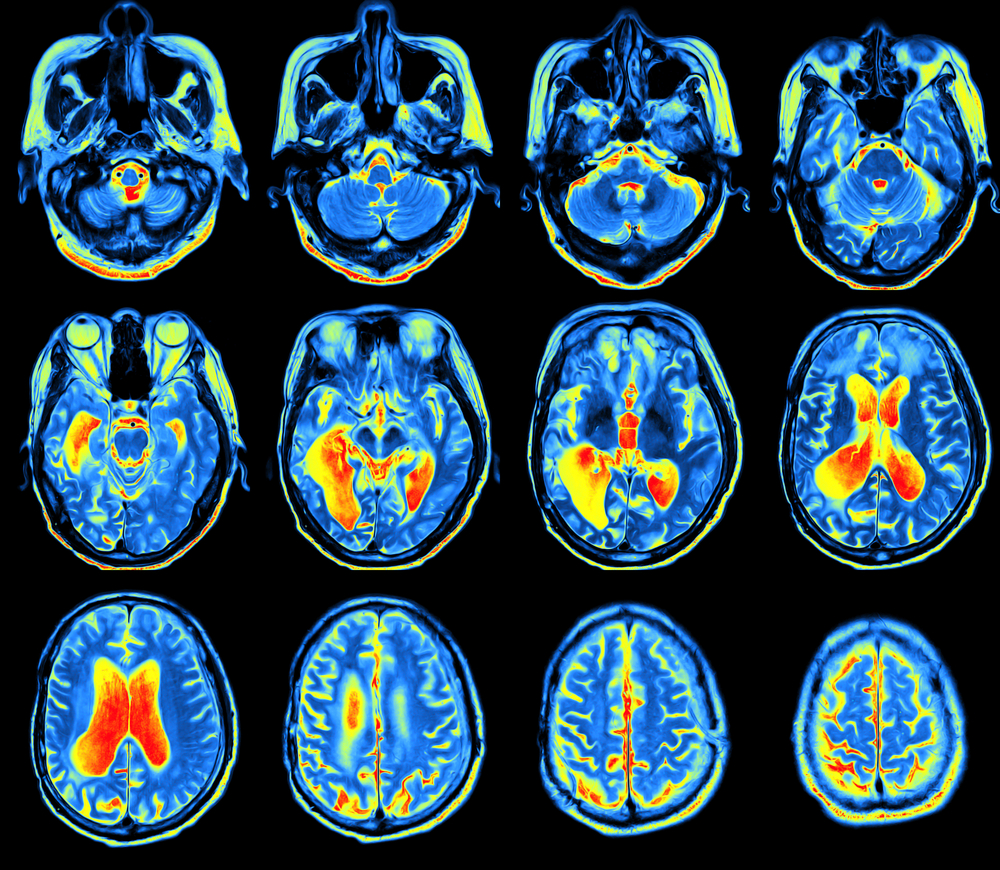

Researchers evaluated how lifestyle factors — including education, the number of languages spoken, reading activity, and frequency with which participants played games such as chess — affected age of disease onset and brain functioning measured by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

They looked specifically at the volume of the brain’s gray matter and the strength of neural connections.

Results showed that high levels of mental activity were significantly associated with better executive functions, a delay in the appearance of symptoms, and a reduction in the shrinkage, or atrophy, of gray matter in certain regions of the brain.

“These patients showed a delay in the appearance of the first symptoms of the disease and a lower level of atrophy in an area of the brain especially affected in this disease, which is called the caudate nucleus,” Clara García Gorro, the study’s first author, said in a press release.

These results suggest that greater mental activity delays the appearance of the first clinical symptoms and less severe cognitive deficits in Huntington’s disease patients.

“Our results are in line with converging evidence in neuroimaging studies that has shown the impact of life experience in brain plasticity, producing changes in gray matter volume and studies on aging and Alzheimer’s disease showing that a more cognitively active lifestyle is associated with lower levels of beta-amyloid pathology,” the researchers wrote in the study.

Importantly, they noted that cognitive engagement can increase both brain resistance and resilience. For example, in Alzheimer’s disease, brain resistance could be associated with a higher clearance of beta-amyloid deposits, while brain resilience could be associated with the preservation of the morphology and development of healthy neurons.

“This discovery emphasizes the importance of cognitive interventions in neurodegenerative diseases, as well as leading a cognitively stimulating life to maintain a healthy brain,” said Estela Càmara, the study’s lead author.