$10.7M NIH Grant to Fund Genetic Research in Alzheimer’s

Genetic

A $10.7-million grant to investigate the genetic underpinnings of Alzheimer’s disease has been awarded to the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health and Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

Despite years of research, scientists have yet to come up with a cure for Alzheimer’s disease — or a way to prevent it. One obstacle to developing treatments is lack of knowledge about the genetic basis of the disease.

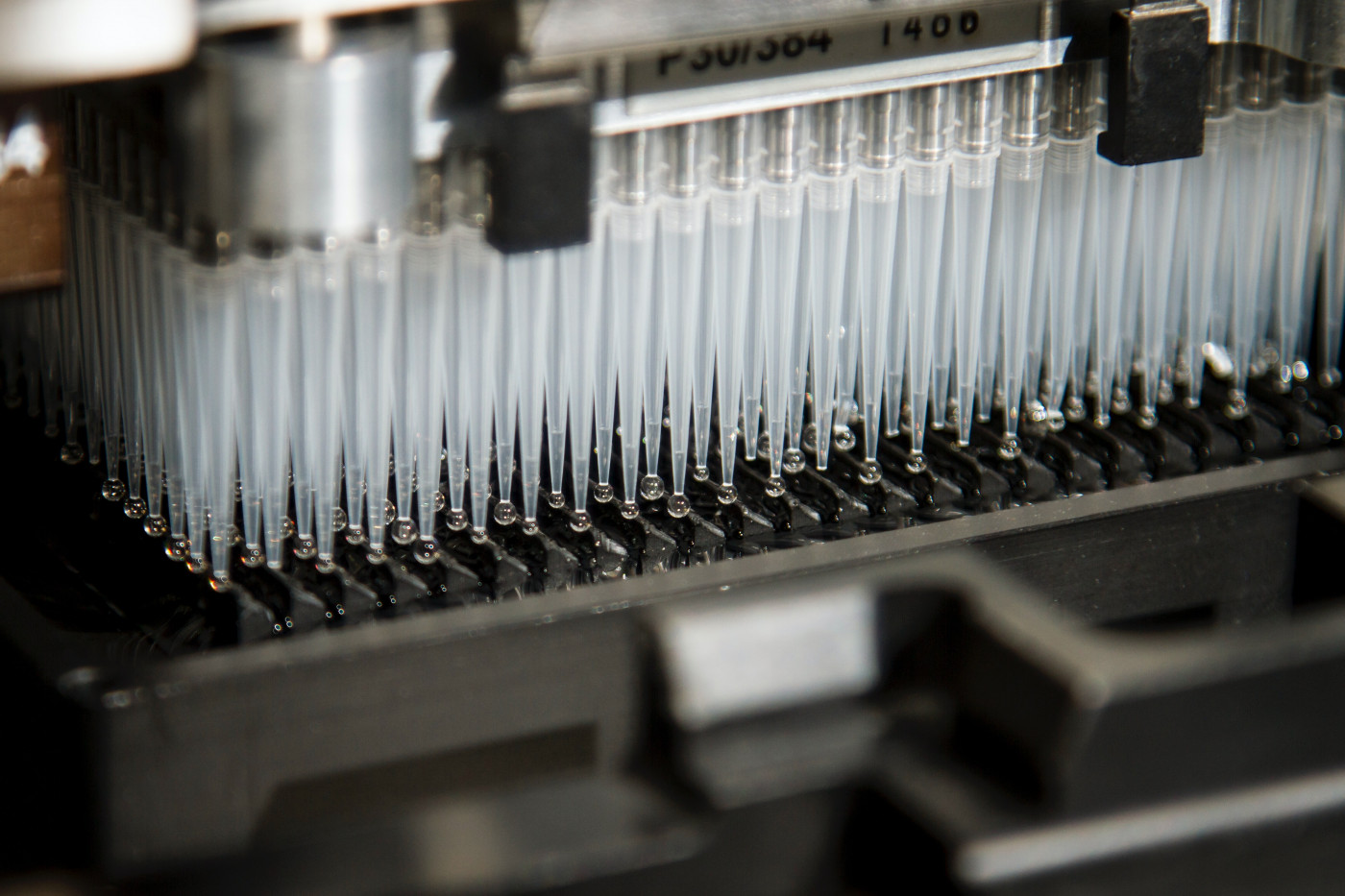

Now, with help from the new five-year grant funded by the National Institute on Aging, a team of researchers will be able to perform the first comprehensive genetic study of Alzheimer’s disease using whole genome sequencing. Whole genome sequencing is a technique that may be used to determine nearly the complete DNA sequence of an individual.

The team will be led by Ilyas Kamboh, PhD, professor of human genetics and epidemiology at Pitt Public Health, and Carlos Cruchaga, PhD, professor of psychiatry at Washington University.

Together, they plan to find the genes — and its variants — involved in the formation of plaques (abnormal clusters of a protein called amyloid-beta) and tangles (twisted strands of another protein called tau).

“All of the clinical trials to find a drug to stop Alzheimer’s disease have failed because they’ve focused on patients who have already developed the disease, so they already had high levels of plaques and tangles,” Kamboh said in a press release.

Plaques and tangles may start accumulating in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease as early as 25 years before symptoms begin, and may be used as biomarkers of disease.

“Once you have the plaques and tangles, it seems to be an irreversible process, so we’re focused on the preclinical stage of the disease,” Kamboh added.

To do so, the researchers are hoping to study up to 5,000 individuals who were recruited from the Pitt and Washington University’s Knight Alzheimer’s Disease Research Centers, who have a high risk for Alzheimer’s disease, and for whom biomarker data are available.

“Plaques and tangles can be used as quantitative traits, which is a more powerful approach to identify genes implicated in disease,” Cruchaga said. “We plan to use the genetic information to create individual-level predictions to determine the risk of someone developing Alzheimer’s disease.”

Currently, the presence of plaques and tangles can be detected through neuroimaging and testing of the cerebrospinal fluid — the fluid which surrounds the brain and spinal cord.

“Previously, we could see these plaques and tangles only after death, through a brain autopsy,” Kamboh said. “Now we can identify them while people are living, but that is done through expensive imaging and invasive testing. New methods also are being developed to detect the presence of abnormal amyloid-beta and tau proteins in less expensive blood tests.”

“Hopefully, by learning more about the genes associated with the plaques and tangles, we can uncover underlying mechanisms of Alzheimer’s disease and discover potential drug targets,” he added.