Aduhelm Approval Greeted With Joy, Concern in Alzheimer’s Community

Written by |

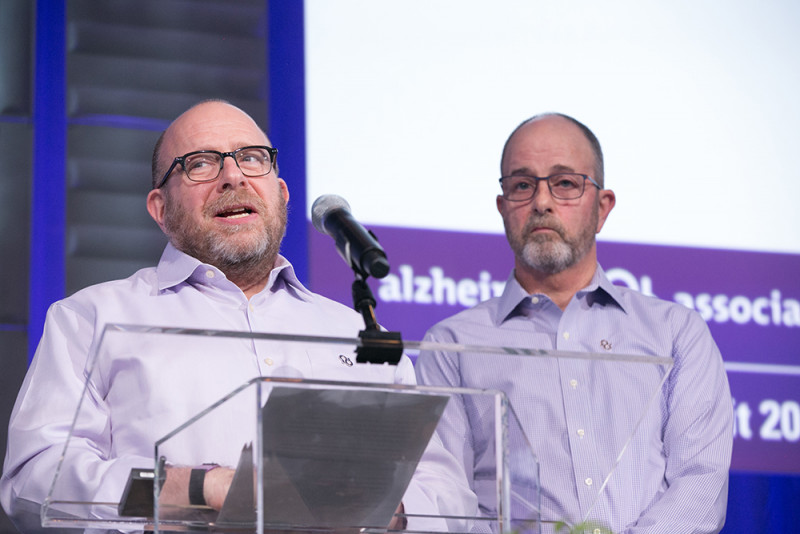

Phil Gutis, left, speaks at an Alzheimer's Association event. (Photo courtesy of Phil Gutis)

A new treatment for people with Alzheimer’s disease — the first approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in nearly 20 years — will be available soon in the U.S. But the reception being given to Aduhelm (aducanumab) is mixed.

Some patients and caregivers welcome the news after years of repeat clinical trial failures and rejections.

Phil Gutis receiving an Aduhelm infusion in the ENGAGE trial. (Photo courtesy of Phil Gutis)

“I was relieved and excited,” said Phil Gutis, 59, an Alzheimer’s patient who was part of the ENGAGE Phase 3 trial (NCT02477800), and entered the open-label EMBARK (NCT04241068) Phase 3 study in June 2020.

“I anticipated that it would be approved,” Gutis said. “So, it didn’t come as a huge surprise.”

Biogen presented promising data at the Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease Conference in December 2019, following a new analysis after its two Phase 3 trials — ENGAGE and EMERGE (NCT02484547) — were halted in March 2019 for likely futility.

Everyone Gutis talked to thought things were going in the right direction, he said. “I think a rejection would have been a much bigger surprise.”

Aduhelm, by Biogen and Eisai, is the first disease-modifying therapy for Alzheimer’s, meaning it is capable of slowing the progression of the disease, and not just its symptoms. The treatment was under the FDA’s accelerated approval program, which allows earlier access to therapies even if there is uncertainty about the clinical benefit.

A Phase 4, or post-marketing, trial to confirm the treatment’s safety and effects also is necessary.

Aduhelm is a human-made antibody designed to remove toxic clumps of the protein beta-amyloid, which are thought to drive the death of nerve cells (neurons) in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s.

“The clinical trials for Aduhelm were the first to show that a reduction in these plaques — a hallmark finding in the brain of patients with Alzheimer’s — is expected to lead to a reduction in the clinical decline of this devastating form of dementia,” the FDA stated in its press release announcing the therapy’s approval.

Gutis said he has noticed cognitive improvements since starting in EMBARK, though changes took a while to develop.

After Biogen stopped ENGAGE and EMERGE due to a planned interim analysis that showed a likelihood of no clinical benefit, Gutis — who was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s shortly before ENGAGE opened in 2015 — was told he was given the infusion treatment at its low, 6 mg/kg dose. Benefit was reported — significantly in ENGAGE — only in patients treated at high dose, up to 10 mg/kg, and this dose is given once a month to all enrolled in EMBARK.

“I just feel like I have a clear head about me, which is really important,” Gutis told Alzheimer’s News Today in a phone interview from his Pennsylvania home.

Since returning to treatment, he said he struggles less for words, can focus on projects again, and is “returning to the land of working.” Before going on disability because of his disease, Gutis was communications director at the Natural Resources Defense Council, a nonprofit environmental advocacy group.

But his husband, Tim Weaver, mentioned noticing more short-term memory issues in recent months. And, while Gutis felt confident improvements were evident in a recent EMBARK trial assessment, in tests he couldn’t name the right date, remember what the long hands of a clock do, or think of more than five words starting with an “s” in one minute.

Rocky road to approval

Aduhelm’s road to FDA approval was tedious. After Biogen stopped its two studies, both in patients with mild disease, a subsequent analysis found EMERGE had met its primary goal. Patients treated at high dose showed a significantly smaller decline in cognitive and functional status — memory, orientation, language, and activities of daily living — over 18 months, relative to those on placebo.

ENGAGE did not, but data suggested benefit to those given Aduhelm at its high dose.

Jason Karlawish, MD, a professor of medicine, medical ethics and health policy, and a neurologist working with Alzheimer’s patients at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine, is among those who opposed Aduhelm’s approval prior to the FDA decision.

He gave his reasons as insufficient trial evidence of benefit, and concern about the precedent approval might set, and doubted he would recommend it to patients.

“The drug may be safe and effective,” he said to Alzheimer’s News Today. “But the results of the two Phase 3 studies just didn’t let themselves lead to that kind of solid conclusion.”

Sanjiv Sharma, MD, founder of the Advanced Memory Research Institute of New Jersey and principal investigator of Aduhelm’s Phase 1b study and both Phase 3 trials, agrees that trial data at face value normally wouldn’t merit approval. But he encourages colleagues to look at the bigger picture.

A needed ‘leap of faith’

In a phone interview, Sharma mentioned that a huge unmet demand for a new and more effective treatment for Alzheimer’s, the sixth-leading cause of death in the U.S. weighs in Aduhelm’s favor. The process of designing and implementing clinical trials is long, likely too long for a disease that progressively destroys a person’s thinking ability and memory, he said.

“It’s kind of a leap of faith by the scientific community,” Sharma said. “Failure of this research was going to dampen the whole research community.”

Another trial failure, given the billions that studies cost, could cause biotech companies to turn away from the disease, leaving the Alzheimer’s community with nothing, he said. From 2002 to 2012, Alzheimer’s trials had an overall success rate of 0.4%, according to a 2014 study published in Alzheimer’s Research and Therapy.

Sharma, however, voiced concern with the broad nature of Aduhelm’s approval. Its FDA label simply calls it an Alzheimer’s treatment based on “reduction in amyloid beta plaques observed.” No specification is given regarding early or late-stage patient use, and there’s no requirement for positron emission tomography (PET) scans to show amyloid plaques in the brain. PET scans help in diagnosing the disease.

“How are you going to say this person is suffering from Alzheimer’s disease before you expose them to IV medication for an unlimited time every four weeks?” Sharma asked. “They’re [FDA officials] not able to answer that.”

Sharma also is troubled by the FDA requiring MRI scans for amyloid-related imaging abnormalities, or ARIAs, a known side effect of Aduhelm, only prior to the seventh and 12th infusions. These abnormalities include ARIA-edema, or fluid accumulation in the brain, and ARIA-H, microhemorrhages and unusual iron deposits known as superficial siderosis.

Two MRIs won’t catch abnormalities that occur after the 12th week, and many local radiologists aren’t trained to read ARIA, Sharma said. But he also noted that edema or microhemorrhage often are not troubling to patients, or particularly dangerous.

Karlawish also was irked by aspects of Aduhelm’s development, particularly its skipping of a Phase 2 trial that should include pharmacological measures of the treatment, and its premature Phase 3 closings that prevented full data collection.

“In the case of studies in the space of Alzheimer’s disease, the one thing we need are complete data sets that explain the actions of the drug, the clinical endpoints, and the biomarkers so we can better understand, in fact, what kinds of biomarkers are adequate surrogates for clinical responses,” Karlawish said.

Karlawish also questions the amyloid hypothesis, which holds that the buildup of beta-amyloid, a small protein fragment, interferes with cell communication in the brain and leads to cell death. He thinks it’s still an “open question,” as more research goes into understanding Alzheimer’s progression.

Treatment cost vs. care cost

Aduhelm’s list price of $4,312 per infusion, which amounts to about $56,000 annually, also is a cause for worry for Karlawish, for patients, and for taxpayers who fund Medicare and Medicaid. Karlawish has said its cost will “stress Medicare’s resources.”

Those resources are already stretched. A 2020 cost study by the Alzheimer’s Association estimated that Medicare and Medicaid spending for Alzheimer’s and other dementias would reach $206 billion that year — 67% of the total budget. And it anticipated that Alzheimer’s care alone could total $584 billion by 2050 as the population ages — an increase of 278% over 30 years that represents “more than 1 in every 3 dollars of total estimated Medicare spending.”

Aduhelm’s “price is simply unacceptable,” the association, which advocated approval, stated in a release. “For many, this price will pose an insurmountable barrier to access, it complicates and jeopardizes sustainable access to this treatment, and may further deepen issues of health equity. We call on Biogen to change this price.”

Sharma, however, considers the cost of care too high not to accept Aduhelm’s price. He noted research is not keeping pace, favoring conditions such as heart disease, cancer, and diabetes. He believes Aduhelm’s success in the approval process will spark more studies and trials, allowing a growing problem to be better addressed before it becomes insurmountable.

“Not finding a cure, not finding a prevention for this is ultimately going to lead to the biggest economic recession in the developed part of the world,” Sharma said.

Gutis recently finished his 52nd Aduhelm infusion, and is looking forward to what new disease research might bring. The year he spent without treatment — between ENGAGE’s close and EMBARK’s start — toyed with his emotions.

“It’s been a real roller coaster of a ride, up and down [and] every which way that you could go,” he said. “But to see us roll over the top of the hill for the next portion of the ride is very exciting.”