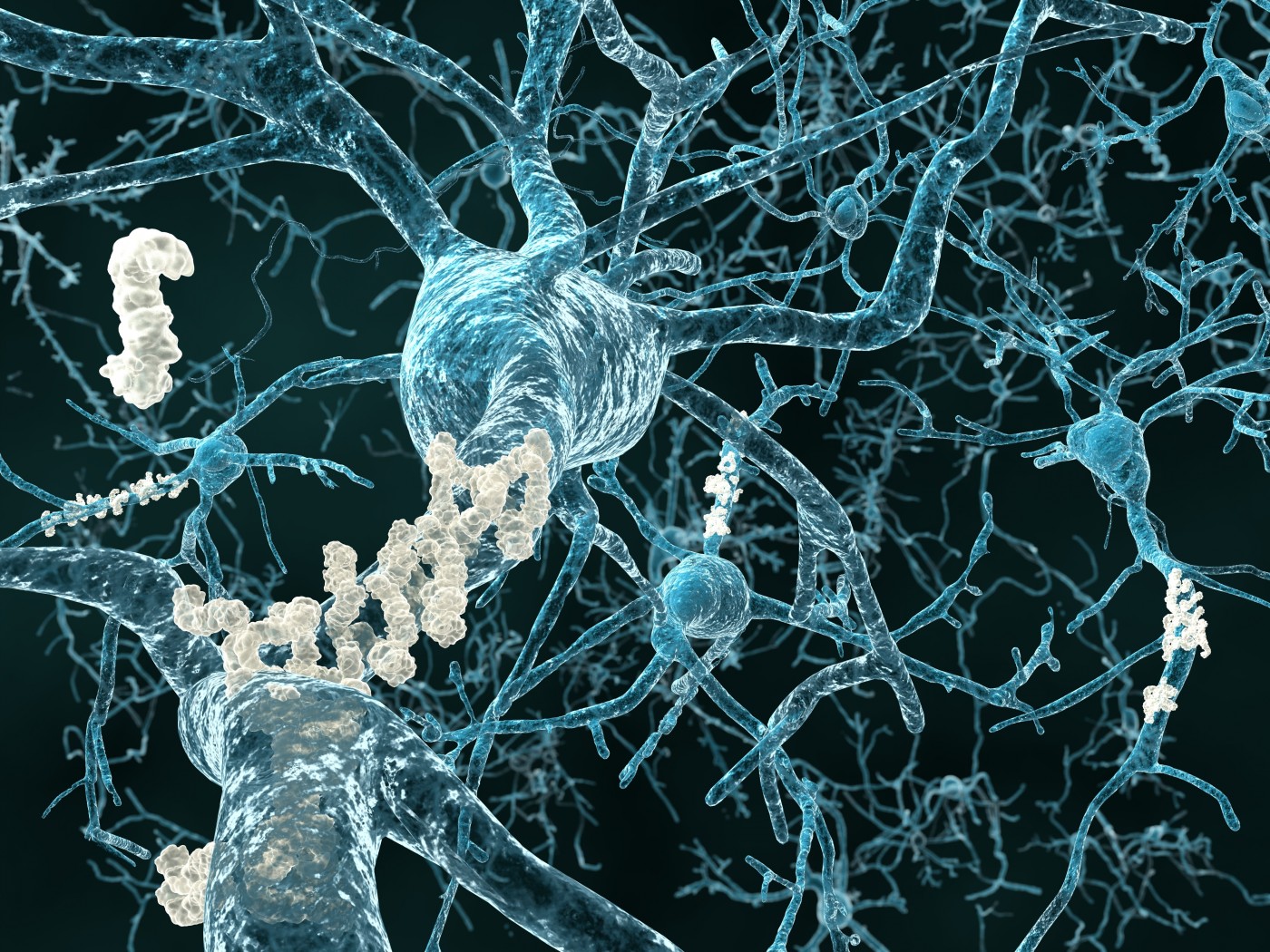

Alzheimer’s Researchers Build Mock Protein That Might Help Them Understand Disease

Written by |

Researchers at the University of Sussex in England have built a protein closely resembling amyloid-β, except for the fact that it is not capable of aggregating.

The new protein, described in a report titled, “A critical role for the self-assembly of Amyloid-β1-42 in neurodegeneration,“ published in the journal of Scientific Reports, will allow researchers to understand the details of how amyloid-β misfolds and accumulates — triggering processes toxic to nerve cells.

Studies in lab dishes and animals suggest that once that the amyloid protein starts clumping together in what scientists refer to as oligomeric forms of the protein, neurodegeneration will soon follow.

Despite enormous research efforts, scientists have, however, not been able to figure out exactly how a misbehaving protein can kill neurons. Studies of the aggregation mechanisms turned out to be more difficult than expected, and the lack of a suitable control protein made interpretation of results difficult.

Up to now, researchers have used proteins folded in a different way, amyloid-β from a rat (that doesn’t aggregate), or simply omitted the protein to construct a control experiment, but such solutions are far from optimal in that they can’t take into account structural features of amyloid-β that might contribute to cell toxicity.

The newly developed protein does not form oligomers (aggregates containing just a few protein molecules) or any other types of protein clumps. In contrast to normal human amyloid-β, the new factor did not disrupt processes within synapses connecting neurons, nor did it cause memory problems in an animal model.

“Understanding how the brain protein amyloid-β causes nerve cell death in Alzheimer’s patients is key if we are to find a cure for this disease,” the study’s first author, Dr. Karen Marshall, said in a news release.

“Our study clearly shows that the aggregation of amyloid-β into bigger species is critical in its ability to kill cells. Stopping the protein aggregating in people with Alzheimer’s could slow down the progression symptoms of the disease. We hope to work toward finding a strategy to do this in the lab and reverse the damaging effects of toxic amyloid-β.”

Senior author Prof. Louise Serpell, the co-director of the University of Sussex’s Dementia Research Group, also believes the mock amyloid-β is a tool that may help researchers find a treatment for Alzheimer’s, and her enthusiasm is shared by Peter Lane, innovation support manager at The Sussex Innovation Centre, working with the research group to commercialize the tool.

“This is a really exciting development. The Centre is thrilled to be working alongside Professor Serpell to make sure the benefits offered by this new laboratory tool are made widely available to the Alzheimer’s research community in the very near future,” Lane said.

But not all scientists are convinced that harnessing the aggregation of amyloid-β is key to a treatment for this debilitating disease. A perspective on the topic, published last year in the journal Nature Neuroscience, pointed out the many inconsistencies with the theory, while other researchers have pointed to the fact that several drug trials have failed to improve cognition despite lowering the amount of amyloid aggregates, urging scientists to widen their view.

Nonetheless, a tool allowing the study of amyloid aggregation still might advance our understanding of the disease processes.