Chance Discovery Of Normal Cognition In Patient Without Apolipoprotein E Could Point To New Alzheimer Treatments

Written by |

A new free access paper published online before print in the journal JAMA Neurology, entitled, “Effects of the Absence of Apolipoprotein E on Lipoproteins, Neurocognitive Function, and Retinal Function” (JAMA Neurol. Published online August 11, 2014. DOI: 10.1001/.jamaneurol.2014.2011) documents a 40-year-old African American man referred to the Lipid Clinic, University of California, San Francisco. The patient was unresponsive to treatment of a rare form of severe dysbetalipoproteinemia (abnormally high levels of cholesterol and triglycerides in the blood), and severe hyperlipidemia, in which cholesterol levels spike to a degree that pools of fatty tissue form under his skin.

A new free access paper published online before print in the journal JAMA Neurology, entitled, “Effects of the Absence of Apolipoprotein E on Lipoproteins, Neurocognitive Function, and Retinal Function” (JAMA Neurol. Published online August 11, 2014. DOI: 10.1001/.jamaneurol.2014.2011) documents a 40-year-old African American man referred to the Lipid Clinic, University of California, San Francisco. The patient was unresponsive to treatment of a rare form of severe dysbetalipoproteinemia (abnormally high levels of cholesterol and triglycerides in the blood), and severe hyperlipidemia, in which cholesterol levels spike to a degree that pools of fatty tissue form under his skin.

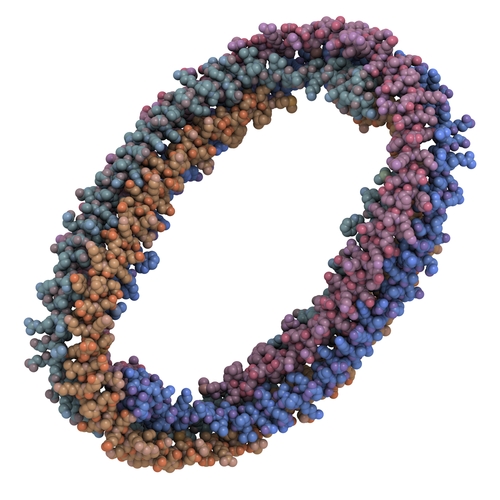

However, this patient, who exhibits normal cognitive function, was also discovered to have no apolipoprotein E (a poE) — a protein made by the APOE gene believed to be important for brain function, but a mutation of which is also a known major risk factor for the most common form of Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

The researchers observed that the patient involved showed no signs or symptoms of any neurological deficit, ophthalmological disease, or cardiovascular disease (CVD). And while the patient was delayed in talking until age 3 years, at school he performed better in mathematics than reading, finishing 11th grade with a C+/B average. His parents and four maternal half siblings have no evidence of CVD. His father, not available for study, is known to be of good health and to have a normal lipid panel. The patient has three healthy children aged four, five, and seven years, and they and his 57-year-old mother have no xanthomas.

The 20 percent of the population who carry one copy of APOE4 have up to five times the risk of developing Alzheimer’s, as do people without that variant, and may develop the disease earlier. The unfortunate two percent demographic that carry two APOE copies have up to 15 times the risk, and 90 percent of people with two copies will develop Alzheimer’s by age 80. Researchers based at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) suggest this could mean that therapies to reduce apoE in the central nervous system may be safe and one day help treat neurodegenerative disorders such as AD.

[adrotate group=”3″]

The study was coauthored by Angel C. Y. Mak, Ph.D., a Postdoctoral Fellow specializing in human genomic data analysis at UCSF, and colleagues Mary J. Malloy, MD; Clive R. Pullinger, PhD; Ling Fung Tang, PhD; Rahul C. Deo, MD, PhD; Irina Movsesyan, BS; Catherine Chu, BS; Annie Poon, BS; Pui-Yan Kwok, MD, PhD; John P. Kane, MD, PhD; Eveline O. Stock, MD; — all of the UCSF Cardiovascular Research Institute; Jinny S. Wong, BS of the Gladstone Institute of Cardiovascular Disease, San Francisco; Jean-Marc Schwarz, PhD and Alejandro Gugliucci, MD, PhD of the College of Osteopathic Medicine, Touro University California, Vallejo; Brian Y. Ishida, PhD, Bela F. Asztalos, PhD, and Ernst J. Schaefer, MD, of Boston Heart Diagnostics, Framingham, Massachusetts; Phillip Kim, MD, of the Darin M. Camarena Health Centers, Madera, California; Joseph M. Castellano, PhD of the Department of Neurology and Neurological Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine; Tony Wyss-Coray, PhD of the Center for Tissue Regeneration, Repair, and Restoration, VA Palo Alto Health Care System, Palo Alto, California; Jacque L. Duncan, MD of the UCSF Department of Ophthalmology; and Bruce L. Miller, MD, of the UCSF Memory and Aging Center.

The study was coauthored by Angel C. Y. Mak, Ph.D., a Postdoctoral Fellow specializing in human genomic data analysis at UCSF, and colleagues Mary J. Malloy, MD; Clive R. Pullinger, PhD; Ling Fung Tang, PhD; Rahul C. Deo, MD, PhD; Irina Movsesyan, BS; Catherine Chu, BS; Annie Poon, BS; Pui-Yan Kwok, MD, PhD; John P. Kane, MD, PhD; Eveline O. Stock, MD; — all of the UCSF Cardiovascular Research Institute; Jinny S. Wong, BS of the Gladstone Institute of Cardiovascular Disease, San Francisco; Jean-Marc Schwarz, PhD and Alejandro Gugliucci, MD, PhD of the College of Osteopathic Medicine, Touro University California, Vallejo; Brian Y. Ishida, PhD, Bela F. Asztalos, PhD, and Ernst J. Schaefer, MD, of Boston Heart Diagnostics, Framingham, Massachusetts; Phillip Kim, MD, of the Darin M. Camarena Health Centers, Madera, California; Joseph M. Castellano, PhD of the Department of Neurology and Neurological Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine; Tony Wyss-Coray, PhD of the Center for Tissue Regeneration, Repair, and Restoration, VA Palo Alto Health Care System, Palo Alto, California; Jacque L. Duncan, MD of the UCSF Department of Ophthalmology; and Bruce L. Miller, MD, of the UCSF Memory and Aging Center.

To investigate the molecular basis of this rare disorder and to determine the effects of complete absence of apoE on neurocognitive and visual function and on lipoprotein metabolism, whole-exome sequencing was performed on the patient’s DNA. He also underwent detailed neurological and visual function testing and lipoprotein analysis. Lipoprotein analysis was also performed in the Cardiovascular Research Institute, University of California, San Francisco, on blood samples from the patient’s mother, wife, two daughters, and normolipidemic control participants.

The coauthors report that they identified a mutation leading to the patient’s apoE deficiency. Extensive studies of the patient’s retinal (eye) and neurocognitive function were performed because apoE is found in the central nervous system and the retinal pigment epithelium of the eye. Despite lacking apoE, the patient had normal vision and exhibited normal cognitive, neurological and eye function. The patient also had normal brain imaging findings and normal cerebrospinal fluid levels of other proteins. Despite complete absence of apoE, he had normal vision, exhibited normal cognitive, neurological, and retinal function, had normal findings on brain magnetic resonance imaging, and had normal cerebrospinal fluid levels of amyloid and tau proteins. The researchers say this suggests that functions of apoE in the brain and eye are not essential or that redundant mechanisms exist whereby its role can be fulfilled suggesting that targeted knockdown of apoE in the central nervous system might be a therapeutic modality in neurodegenerative disorders.

The researchers note that: “Failure of detailed neurocognitive and retinal studies to demonstrate defects in our patient suggests either that the functions of apoE in the brain and eye are not critical or that they can be fulfilled by a surrogate protein. Surprisingly, with respect to central nervous system function, it appears that having no apoE is better than having the apoE4 protein. Thus, projected therapies aimed at reducing apoE4 in the brain could be of benefit in neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer disease.”

In a related editorial, Courtney Lane-Donovan, S.B., and Joachim Herz, M.D. , of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, write: “More than 20 years ago, a polymorphism in the apolipoprotein E (apoE) gene was identified as the primary risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer disease (AD). Individuals carrying the 4 isoform of apoE (apoE4) are at significantly greater risk for AD compared with apoE3 carriers, whereas the apoE2 allele is associated with reduced AD risk.”

In a related editorial, Courtney Lane-Donovan, S.B., and Joachim Herz, M.D. , of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, write: “More than 20 years ago, a polymorphism in the apolipoprotein E (apoE) gene was identified as the primary risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer disease (AD). Individuals carrying the 4 isoform of apoE (apoE4) are at significantly greater risk for AD compared with apoE3 carriers, whereas the apoE2 allele is associated with reduced AD risk.”

“Despite two decades of research into the mechanisms by which apoE4 contributes to disease pathogenesis, a seemingly simple question remains unresolved: is apoE good or bad for brain health? The answer to this question is essential for the future development of apoE-directed therapeutics. In light of apoE as the primary risk factor for AD, the lack of neurological findings in this patient would appear to answer the question of whether apoE is necessary for brain function with a resounding no,” they continue.

“Overall, the patient’s normal cognitive function together with the earlier mouse work suggest that interventions that reduce cerebral apoE levels may hold promise as a potential therapeutic approach to AD,” Mr. Donovan and Dr. Herz conclude.

For more information, the original investigation is available at:

https://archneur.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=1893443&resultClick=1

Sources:

JAMA Neurology

The JAMA Network Journals