Funding Renewed for Long-term Study of Adult Children of Alzheimer’s Patients

Washington University researchers have received a $10.3 million grant renewal to continue a long-term study of adults who are more susceptible to developing Alzheimer’s because their parents had it.

The team is trying to define which of these adults is likely to develop the disease — and when — and to establish a timeline for how quickly it may progress.

The project at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis began in 2005 with funding from the U.S. National Institute on Aging. The Adult Children Study has already helped identify some of the molecular and structural changes in the brain that take place decades before a person is diagnosed with Alzheimer’s.

The grant renewal will allow the team to extend the study for another five years and to include new goals and methods in it.

Medicine has already discovered that the sons and daughters of Alzheimer’s patients are at higher risk of developing the disease themselves. But scientists don’t know how to predict which adult children will develop it, or at what age their symptoms will appear.

“Our participants want to know if and when they will experience symptoms such as memory loss,” Dr. John C. Morris, the principal investigator of the study, said in a university news story written by Tamara Bhandari. “We anticipate that in the next five years we can begin to tell them.”

Morris thinks that some day people on track to develop the disease can be directed into clinical trials of investigational drugs that could delay or even prevent the onset of symptoms. While an Alzheimer’s treatment has yet to become available, knowing the risk of developing it could lead to better-informed decisions for dealing with it.

“You might choose to move to an independent-living environment that also provides nursing care. You might choose to move closer to your children,” said Dr. Tammie Benzinger, an associate professor of radiology who directs medical imaging studies at Washington University’s Knight Center.

The study’s objective is to identify who is susceptible to the disease before it starts affecting them and those around them. In addition, people who are healthy but at increased risk of developing the disease represent an ideal population for testing preventive therapies.

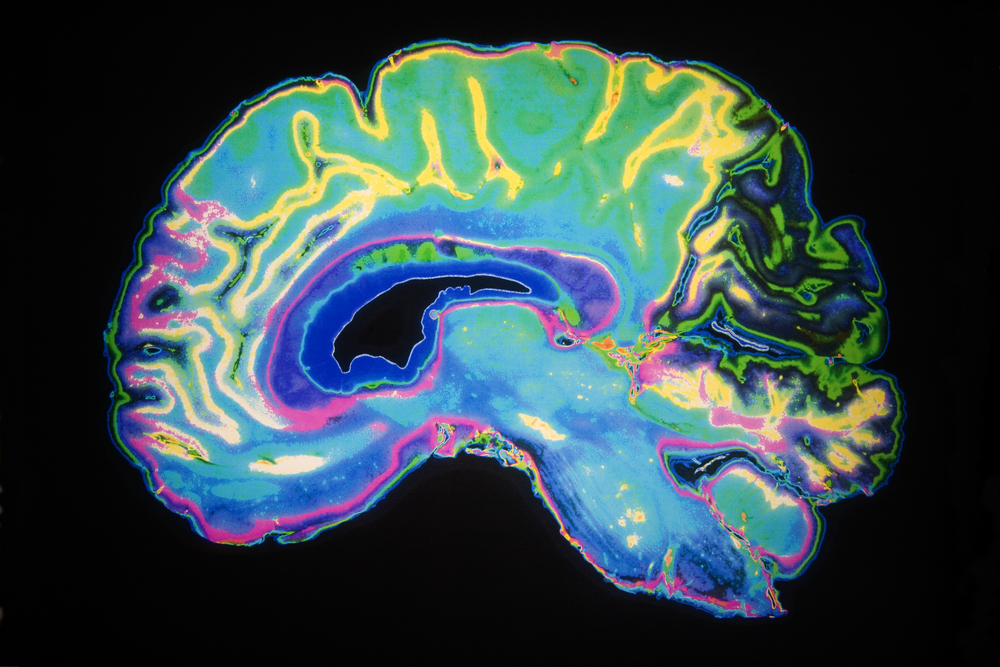

Every three years, researchers measure the study participants’ memory and thinking abilities. They also perform brain scans to assess participants’ levels of the Alzheimer’s-related proteins tau and amyloid beta. The new funding will help researchers compare two new imaging compounds that might do a better job of detecting the two proteins.

Another new wrinkle in the study in the next five years is that instead of patients coming to the Knight Center for memory and cognition tests, they’ll be able to do it from home. That’s because the research team has developed mobile phone technology that allows patients to test their memory and thinking from a smartphone.

The overall goal of the next phase of the project is to develop criteria that can help doctors predict the onset and course of the disease 15 to 20 years before brain damage leads to symptoms. With these criteria, researchers hope to be better equipped to design clinical trials of therapies that can prevent or delay Alzheimer’s.

“By the time symptoms bring people into the clinic, their brains are already atrophied,” said Dr. Anne Fagan, a professor of neurology who leads the biomarker part of the study. “It is highly unlikely that any sort of intervention is going to bring back neurons [nerve cells] that have died. But if we can identify people with underlying pathology while their thinking skills are still intact, we can put them in clinical trials to try to stop, or maybe even reverse, the disease process.”

Morris is recruiting new participants between 45 and 74 years old who have no problems with memory or thinking. Most of the participants enrolled so far are at higher risk of developing the disease because one or both of their parents has had it, or has it now. Adults whose parents have never had Alzheimer’s are serving as the comparison group in the study.