Difficulty in Identifying Subtle Image Differences May Hint at Future Likelihood of Alzheimer’s, Researchers Suggest

People who have trouble detecting details in a test with figures may be at increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease later in life, according to a new study. This finding suggests that subtle changes in cognition may be identified long before more common symptoms of Alzheimer’s appear.

The study, “Family History of Alzheimer’s Disease is Associated with Impaired Perceptual Discrimination of Novel Objects,” appeared in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Clinical manifestations of Alzheimer’s disease can take years to become fully visible, noted Emily Mason, a postdoctoral associate in the Department of Neurological Surgery at Kentucky’s University of Louisville.

“Right now, by the time we can detect the disease, it would be very difficult to restore function because so much damage has been done to the brain,” Mason, PhD, the study’s first author, said in a news release. “We want to be able to look at really early, really subtle changes that are going on in the brain. One way we can do that is with cognitive testing that is directed at a very specific area of the brain.”

In their study, researchers tested how adults 40 to 60 years old with normal cognition, but at increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease due to family history, performed in a cognitive task known to activate a brain area called the perirhinal cortex. Results were compared to those of participants with no family history of Alzheimer’s.

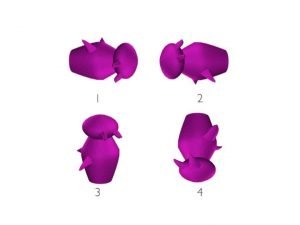

During the test, participants viewed sets of four images of real-world objects, human faces, scenes and Greebles (fine details added to the surface of a larger object that makes it look more complex). Among the four images, one was slightly different from the other, and researchers asked participants to identify which image was the “odd man out.|

Both groups performed similarly for the objects, faces and scenes, but the group of at-risk participants had more difficulty identifying the different image compared to the other group. Indeed, the at-risk group answered correctly 78 percent of the time, whereas the other participants detected the different greeble 87 percent of the time.

“Most people have never seen a Greeble and Greebles are highly similar, so they are by far the toughest objects to differentiate,” Mason said. “Using this task, we were able to find a significant difference between the at-risk group and the control group. Both groups did get better with practice, but the at-risk group lagged behind the control group throughout the process. The best thing we could do is have people take this test in their 40s and 50s, and track them for the next 10 or 20 years to see who eventually develops the disease and who doesn’t.|

Researchers cautioned that this test is not definitive in detecting Alzheimer’s, but may help clinicians identify which at-risk subjects may develop the disease over time.

“We are not proposing that the identification of novel objects such as Greebles is a definitive marker of the disease, but when paired with some of the novel biomarkers and a solid clinical history, it may improve our diagnostic acumen in early high-risk individuals,” said Brandon Ally, PhD, the study’s senior author. “As prevention methods, vaccines or disease modifying drugs become available, markers like novel object detection may help to identify the high priority candidates.”