Heart Drug May Work to Treat Alzheimer’s By Preventing Plaque Build-Up in Brain

Written by |

Swedish researchers demonstrated that a heart medication can reduce the build-up of plaque in brain blood vessels in mice. If findings in this animal study hold true for humans, scientists may be closer to developing a drug against Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The study, “Platelets contribute to amyloid-β aggregation in cerebral vessels through integrin αIIbβ3–induced outside-in signaling and clusterin release,” was published in the journal Science Signaling.

Researchers at Örebro University, working in collaboration with Italian and German scientists, found a previously unknown mechanism to be the origin of fast plaque build-up in blood vessels in the brain. They also conducted experiments in mice to determine whether a specific heart medication is capable of reducing plaque formation.

“You should be careful not to draw any major conclusions from experimental studies, but we have certainly identified an interesting approach worth taking further,” Professor Magnus Grenegård of Örebro University said in a news release.

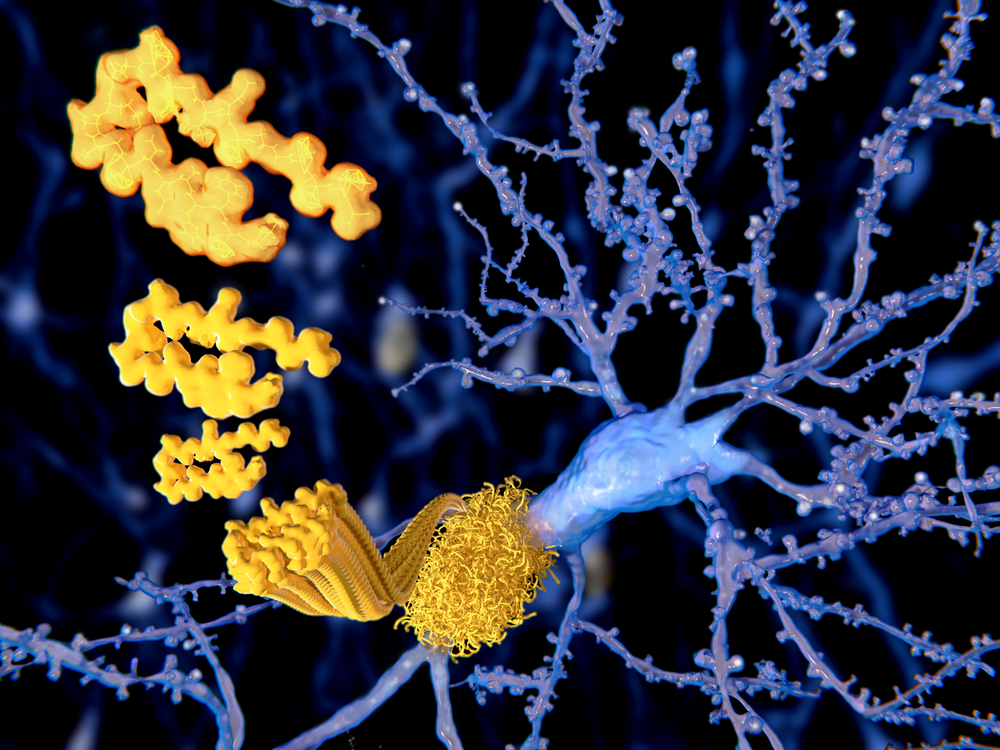

The scientists showed that the beta-amyloid protein sticks to the surface of blood platelets (thrombocytes), instigating a rapid chain reaction and leading to a quick build-up of plaque. “Plaque causes nerve cells to die at too fast a rate, causing the symptoms indicative of Alzheimer’s disease, such as memory loss,” said Professor Grenegård. “Our study is an example of solid biomedical basic research at the cell and molecular levels which points to a link that was previously unknown. What is shown is that cells in the blood may play a significant role in the development of plaque, which is found in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.”

Researchers investigated a drug commonly used to decrease the risk of heart attacks and prevent blood clots. In their experiments with mice, they found that when rodents were treated with the drug, clopidogrel (an antiplatelet agent), there was a decrease in the plaque build-up process.

“In deep structures of the brain, where certain memory functions are controlled, there was a clear trend of reduced plaque presence,” Professor Grenegård added. “We do not know if this is transferrable to humans; if the effect would be the same. To find out, new follow-up studies are required. Unfortunately, this is a lengthy process — it will be years before we know. But at least we have identified a new, interesting approach with respect to plaque formation.”