New Test Directly Measures Loss of Synapses in Alzheimer’s Patients

Researchers from Yale University have developed a new test that measures changes in synapses, which is the structure that allows neurons to communicate with other neurons or cells through electrical/chemical signals.

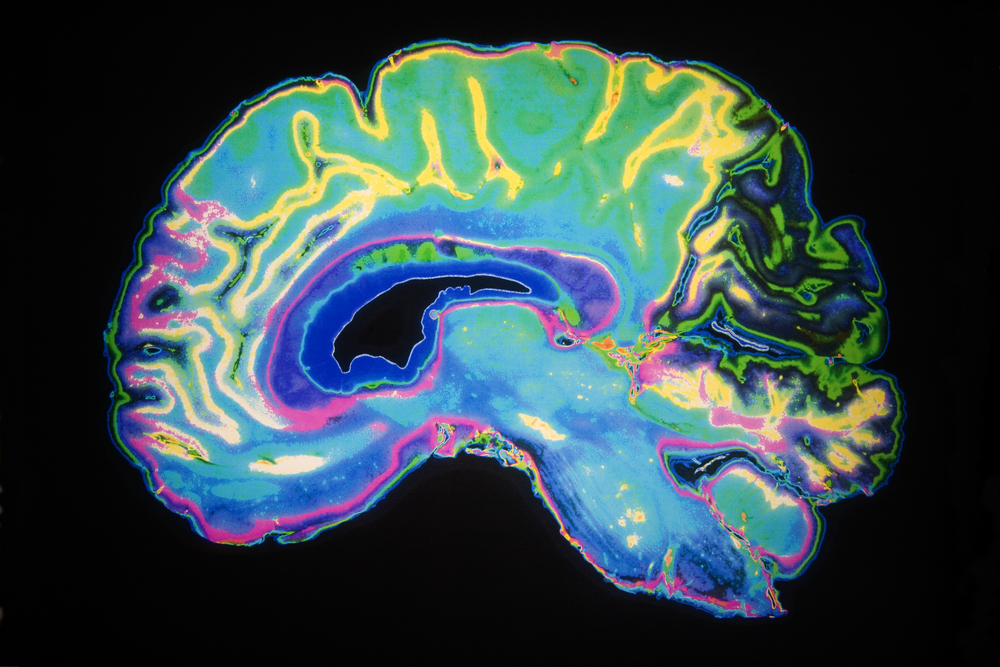

The technique uses positron emission tomography (PET) imaging technology to measure the activity of a specific protein linked to synapses. Synaptic loss is an established indicator of cognitive decline.

The study was a collaborative project between researchers at the Yale PET Center and the Yale Alzheimer’s Disease Research Unit (ADRU). The results from the study, “Assessing Synaptic Density in Alzheimer Disease With Synaptic Vesicle Glycoprotein 2A Positron Emission Tomographic Imaging,” were published recently in the journal JAMA Neurology.

Alzheimer’s disease often is viewed as a progressive disease that starts preclinical, moves to mild cognitive impairment, and finally to Alzheimer’s dementia. As the disease progresses, specific molecular characteristics also become apparent. These molecular features include the development of β-amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and loss of synapses. Synapses are critical for cognitive function and memory.

Although Alzheimer’s affects 5.7 million Americans — with numbers expected to increase dramatically over the next 30 years — much of the research on the disease relies on autopsies. A way to measure synapses in living patients is necessary to better understand this disease and to develop new treatments.

The synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A (SV2A) is a vesicle membrane protein that is found in almost all synapses. Its expression could be a suitable marker of synaptic density.

To look at SV2A expression in living patients, researchers used PET imaging. PET imaging uses radioactive tracers (radionuclides) to measure metabolism in specific regions of the body. By using a radionuclide that binds to SV2A (namely 11C-UCB-J), PET scans can measure the density of SV2A in the brain.

Twenty-one elderly participants, including 10 with Alzheimer’s and 11 who were cognitively normal, were included in the study. Participants in the Alzheimer’s group covered the spectrum of diseases, including patients with mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s dementia. The average age of that group was 72.7 years, and that of the cognitively normal group was 72.9 years.

All participants received one injection of 11C-UCB-J followed by PET imaging.

Researchers found that 11C-UCB-J binding was significantly reduced in the hippocampus of participants with AD, compared with participants who were cognitively normal, suggesting loss of SV2A and synaptic density in this region. The hippocampus has a major role in learning and memory.

After normalizing to a region in the brain where no synaptic loss would be expected, researchers found a 41 percent reduction of SV2A binding in patients with Alzheimer’s, compared to the cognitively normal group. This difference was maintained even after controlling for loss of brain tissue due to atrophy in patients with the disease.

In addition, the levels of 11C-UCB-J binding also correlated with episodic memory. When SV2A-PET scans showed lower 11C-UCB-J binding, suggestive of loss of SV2A expression and synaptic loss, participants also had lower memory.

“We found that in early Alzheimer’s disease, there is loss of synaptic density in the region of the hippocampus,” Ming-Kai Chen, MD, the study’s first author, said in a Yale press release written by Ziba Kashef.

“With this new biomarker, PET imaging for SV2A, we can measure synaptic density in the living human brain,” Chen added.

Due to the limited size of the study, researchers at Yale are currently recruiting more participants to confirm their findings.

According to the team, if proven valid, this test may become a valuable tool for monitoring response to treatment in clinical trials in diseases characterized by synapse loss.

“For those of us in the Alzheimer’s field, in vivo assessment of synaptic density may transform our ability to track early Alzheimer’s pathogenesis and response to treatment,” concluded Christoper Van Dyck, MD, director of the ADRU.