Traumatic Brain Injury Linked to Parkinson’s But Not Alzheimer’s in Large Study

Written by |

Ever since Dr. Bennet Omalu, who Will Smith portrayed in the movie “Concussion,” released his 2005 study — based on autopsy results from a former professional football player — that revealed “neuropathological changes consistent with long-term repetitive concussive brain injury,” the future cognitive impact of traumatic brain injury (TBI) has become a keen interest in the field of clinical neurology and public health.

Research focused on TBI and the subsequent associated loss of consciousness (LOC) has suggested that there is a link between these injuries and the decline of brain function, but very few studies show a definitive correlation between TBI with LOC and the future development of either Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s disease.

To fill this data “gap,” researchers from Mount Sinai conducted a study of head injury data from 7,130 older adults, free of dementia at baseline, to investigate associations between TBI and late-life clinical outcomes, such as dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment, and Parkinson’s disease. Data were accrued from 1994 to April 1, 2014. Results showed an association between TBI in some individuals — those who had lost consciousness after injury for more than hour — and Parkinson’s disease, but not Alzheimer’s.

The study, “Association of Traumatic Brain Injury With Late-Life Neurodegenerative Conditions and Neuropathologic Findings”, was published in the latest issue of JAMA Neurology.

The study group, the largest yet assessed for this topic, underwent cognitive and clinical testing once or twice a year, and included 865 people who had suffered TBI with LOC prior to the start of the research. Of these participants, 142 had loss of consciousness following an injury for more than one hour. Brain autopsies were done on close to 23 percent of the total group, or 1,589 people.

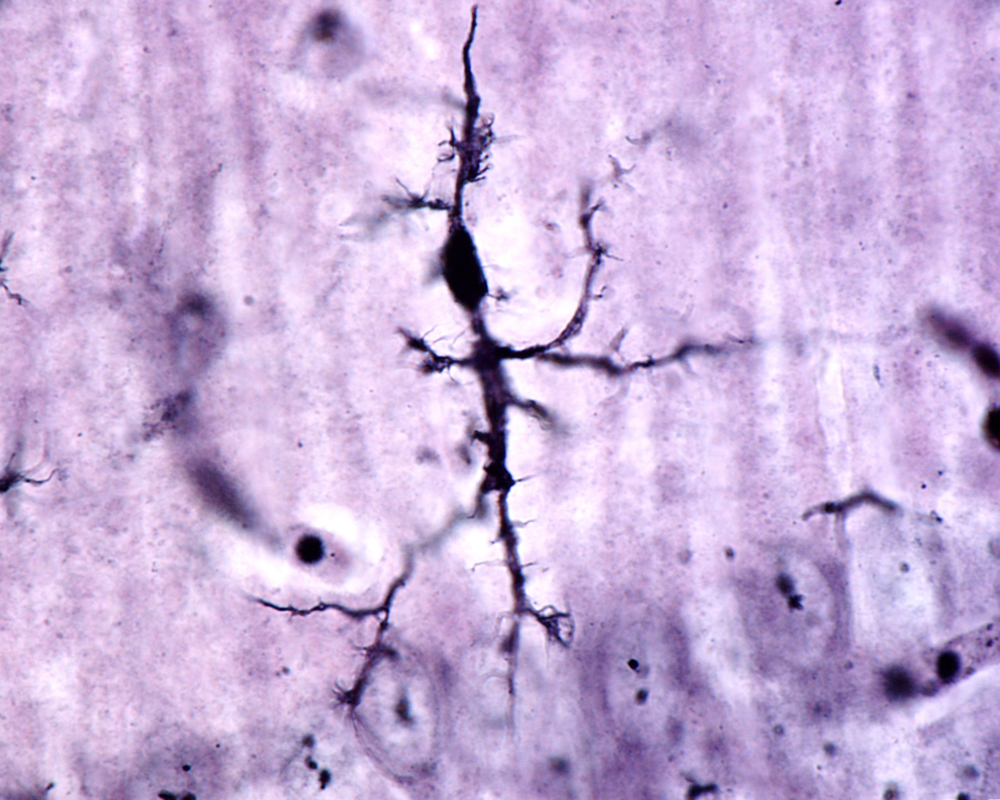

Such autopsies are paramount for this type of research, allowing the investigators to determine post-mortem whether a link exists between TBI and neuropathological findings.

After analysis of the available data, the researchers concluded that TBI with LOC is strongly associated with the development of Parkinson’s disease in those who lost consciousness for more than an hour. But no significant association was found with Alzheimer’s disease (no link between TBI with LOC and amyloid plaques or neurofibrillary tangles, hallmark indicators of Alzheimer’s that the researcher hypothesized they would find).

These findings are not only important to individuals who have suffered previous TBIs with LOC and were worried about Alzheimer’s disease later in life, they are also of significance for healthcare providers who may in the past have treated late-life TBI-related neurodegeneration as Alzheimer’s disease, in which case treatment protocols would not be effective.

“The results of this study suggest that some individuals with a history of TBI are at risk for late-life neurodegeneration but not Alzheimer’s disease,” Kristen Dams-O’Connor, PhD, co-director of the Brian Injury Research Center and an associate professor in the Department of Rehabilitative Medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine, said in a Mount Sinai press release. “We want to identify and treat post-TBI neurodegeneration while people are still alive, but to do this, we need to first understand the disease. Prospective TBI brain donation studies can help us characterize post-TBI neurodegeneration, identify risk factors, and develop effective treatments.”