Promising Therapeutic Strategy for Alzheimer’s Disease Based on Specific Immune Cells

Researchers at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center recently published in the journal Brain a new promising immune therapeutic strategy for Alzheimer’s disease using mice models. The study is entitled “Therapeutic effects of glatiramer acetate and grafted CD115+ monocytes in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease”.

Alzheimer’s disease is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by cognitive and behavioral problems. It is the most common form of dementia in the elderly with patients initially experiencing memory loss and confusion that gradually leads to behavior and personality changes, a decline in cognitive abilities and ultimately to severe loss of mental function. Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by the brain formation of amyloid plaques (composed of beta-amyloid proteins), and the loss of the connection between neurons that are responsible for memory and learning leading to their eventual death.

It has been previously reported that immune cells upon exposure to high concentrations of the toxic beta-amyloid protein in the brain can no longer attack and resolve plaque formation. As disease progresses, these immune cells turn defective, becoming themselves toxic to the neurons and contributing to the detrimental inflammation process.

“These cells appear to work in the brain in several ways to counter the negative effects associated with Alzheimer’s disease,” explained the study’s senior author Dr. Maya Koronyo-Hamaoui in a news release. “The increasing incidence of Alzheimer’s disease and the lack of any effective therapy make it imperative to explore new strategies, especially those that can target multiple abnormalities in such a complicated disease,”

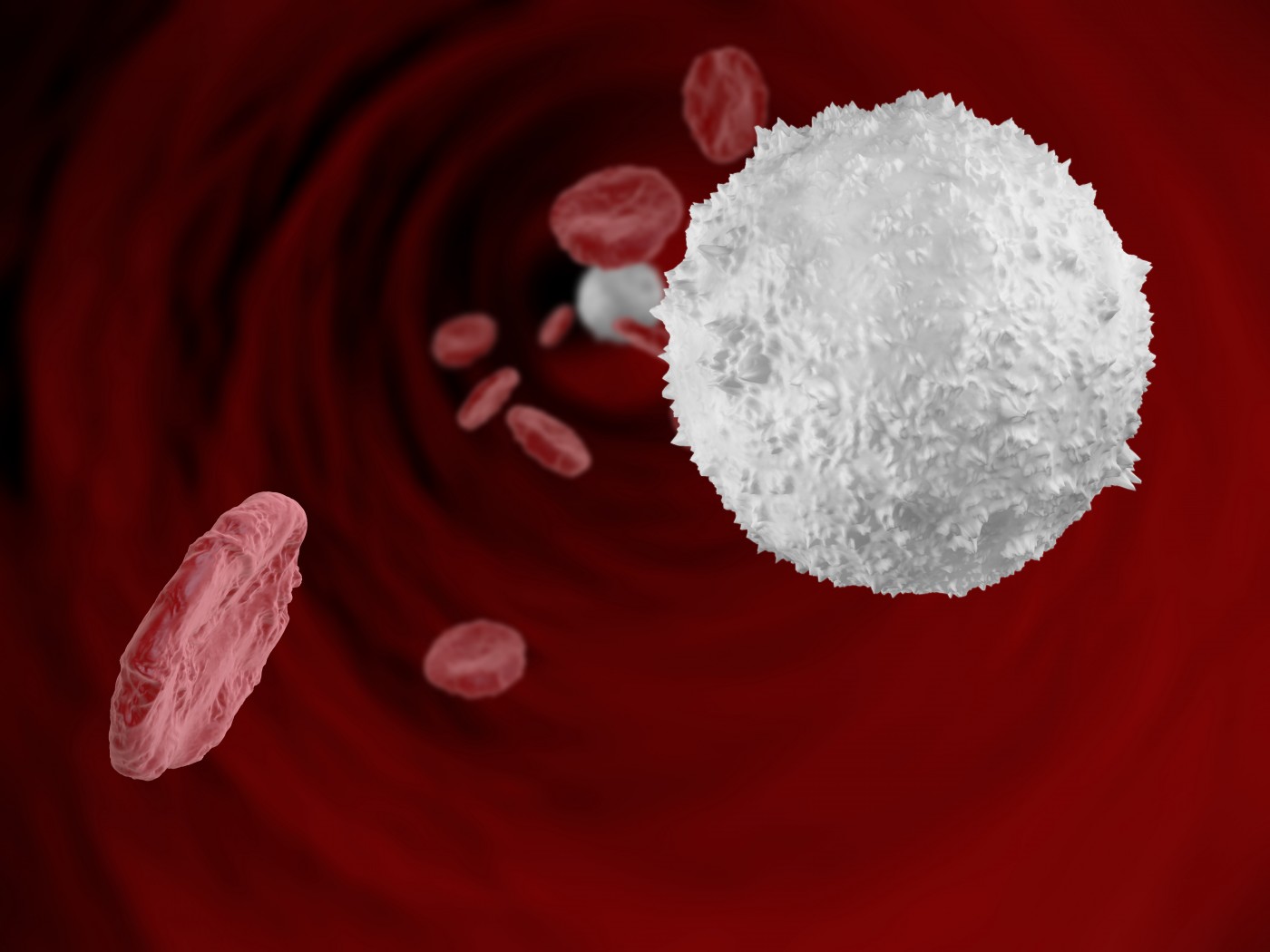

In order to enhance an effective immune response, researchers have developed two methods that they tested in mice models of Alzheimer’s disease. One is to recruit specific monocytes (white blood cells) that would attack the beta-amyloid protein fragments in the brain preserving neuron communication. Researchers did this by extracting CD115+ monocytes from the bone marrow of healthy animals and injecting them in sick mice once a month. On the second method, the team used the glatiramer acetate drug which has been approved for the treatment of multiple sclerosis, also a neurodegenerative disorder. The drug has been shown to stimulate the migration of white blood cells from the bloodstream to the brain and control the immune response. Glatiramer acetate was weekly injected under-the-skin of sick mice. The team also tested both methods combined in a third group of sick mice.

Researchers found that all three treatment strategies had a clinical benefit in preserving animal’s cognition and reducing Alzheimer’s-like pathology and symptoms. All treatments effectively recruited monocytes to lesion sites in the mouse brain, eliminating protein plaques and mitigating inflammation. The combination of both grafted monocytes and glatiramer acetate further enhanced the recruitment of monocytes to the brain.

“This study provides the evidence that a subgroup of unmodified monocytes, extracted from the bone marrow of healthy mouse donors and grafted into the bloodstream, can migrate into the brains of sick mice, directly clear abnormal protein accumulation and preserve cognitive function,” noted the study’s lead author Yosef Koronyo.

The research team concluded that an increase in brain infiltration of monocytes, either by enrichment of their levels or through glatiramer acetate treatment, substantially mitigated disease progression in Alzheimer’s mouse models by promoting the degradation of beta-amyloid plaques and regulation of brain inflammation.