Documentary Chronicles Father’s Battle With Alzheimer’s

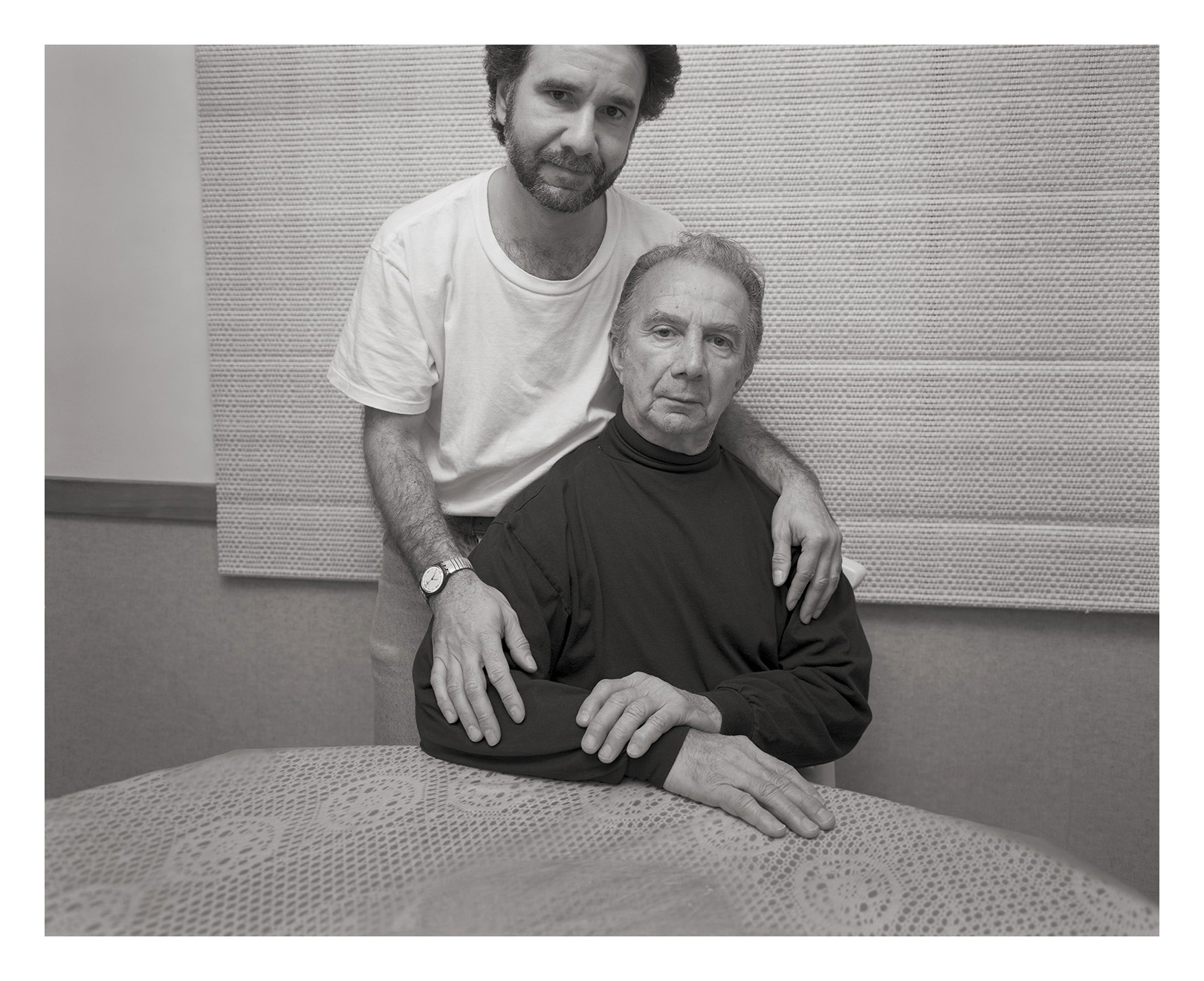

Photo courtesy of Stephen DiRado

Stephen DiRado and his father, Gene DiRado, in a self-portrait taken with a large format camera.

A new documentary released in advance of World Alzheimer’s Day today tells the story of a Worcester, Massachusetts, photographer and art professor who captured the gradual cognitive decline of his late father through a large format black-and-white camera.

“With Dad,” which is available to stream on the local Boston TV and radio station website GBH and will air locally at 7:30 p.m. tonight (Tuesday) tells the story of Stephen DiRado’s father’s battle with Alzheimer’s disease as told through the powerful lens of his son’s art. DiRado released a book with the same name in late 2019.

“I wanted to make something that people could look back upon the thing that at one time called Alzheimer’s existed, how hideous it was,” said DiRado, 64, a Worcester resident and professor of practice in photography at Clark University, in an interview with Alzheimer’s News Today. “It was bigger than us.”

The bulk of the 29-minute documentary, directed by Søren Sørensen, a colleague of DiRado’s at Clark University, bounces between an interview with DiRado, overhead shots of him pointing out items in his photos, the still images he captured of his late father, Gene DiRado, and footage that his brother, Chris DiRado, started to capture when Gene was moved to a nursing home after his second stroke.

“With Dad” has seen a success on the independent film festival circuit, taking the award for Best Short Documentary at the NYC Independent Film Festival, Best Documentary at the Massachusetts Independent Film Festival, and Best Short Documentary at the Red Dirt Film Festival.

It moves chronologically through Gene’s Alzheimer’s progression from the mid-’80s, when DiRado first noticed something was off, to his eventual diagnosis in 1998 to his death on Dec. 11, 2009.

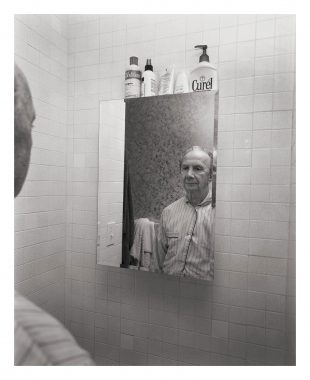

Gene DiRado looks at himself in the mirror on Nov. 2, 2003. (Photo courtesy of Stephen DiRado)

Stephen DiRado had taken family portraits for nearly his whole life after Gene, also a professional artist, gave him his first camera. When Gene began to show early signs of Alzheimer’s, before the family even knew what the disease was and long before he was diagnosed, DiRado decided to focus solely on his father using the large, antiquated-looking black-and-white film camera. He started making photography appointments with him, having him pose in the backyard or at the beach or at the dinner table, creating 3,000 photos in total.

In one photograph shortly before Gene was transferred to a nursing home, he regards himself in the mirror and doesn’t seem to recognize the man looking back at him. It was a turning point both in the documentary and in DiRado’s career as an artist — he was photographing someone who could not give verbal consent.

“It’s one of those moments in your life that is just so tragic, so hideous, that you just want to crawl up in a corner someplace and put a blanket over your body for the next five days,” DiRado said. But he didn’t give in. “No, I have to continue making these photos.”

Talks to make the documentary began while DiRado was still working on the “With Dad” book. Sørensen and DiRado had met in 2016 while Sørensen was a visiting professor at Clark. Two years later, when Sørensen had to make a decision about his limited residency program at the Vermont College of Fine Arts, he thought back to DiRado and his photographs, envisioning a documentary relying solely on two shots — DiRado talking directly to the camera and an overhead shot of him handling his photos.

But Sørensen later found out about the video footage DiRado’s brother had shot and quickly altered his two-shot dogmatic approach to the film.

“Once I found out Chris had shot all this contemporaneous video footage, then it was out the window,” Sørensen said. “I’m going to make this as big and bold as I can and use all the tricks of narrative storytelling and filmmaking and whatever else I can figure out to sort of get inside the story.”

DiRado set up Chris with a digital video camera to help give him something to do when visiting Gene, as it was difficult for him to feel comfortable being there. It turned out this task gave him a clear purpose of documenting DiRado’s emotional black-and-white photographs, and hundreds of hours of footage were available to Sørensen. Because of that, the documentary gives viewers a unique look into DiRado’s family life and his artistic process.

One scene particularly encapsulated the artist at work. While filming the setup for one photo, Chris is holding up the bounce, which points the sunlight at a subject (in this case his mother, Rose, seated behind Gene), DiRado is tinkering with the monstrous camera, and Rose is alerting the group as to when the light hit her face. It was a family effort that lasted to the end.

Gene’s last day was bittersweet for DiRado. On one hand, he was leaving his family, but on the other he was moving on, leaving a body that had failed him. He didn’t take any photos that day.

“My job was over; it was not about the outcome,” DiRado said, mirroring a theme present throughout the film. “It was about the process, what Alzheimer’s was doing to him and the community.”