Cognitive Difficulties Can Predict Neurodegeneration, Study Finds

Written by |

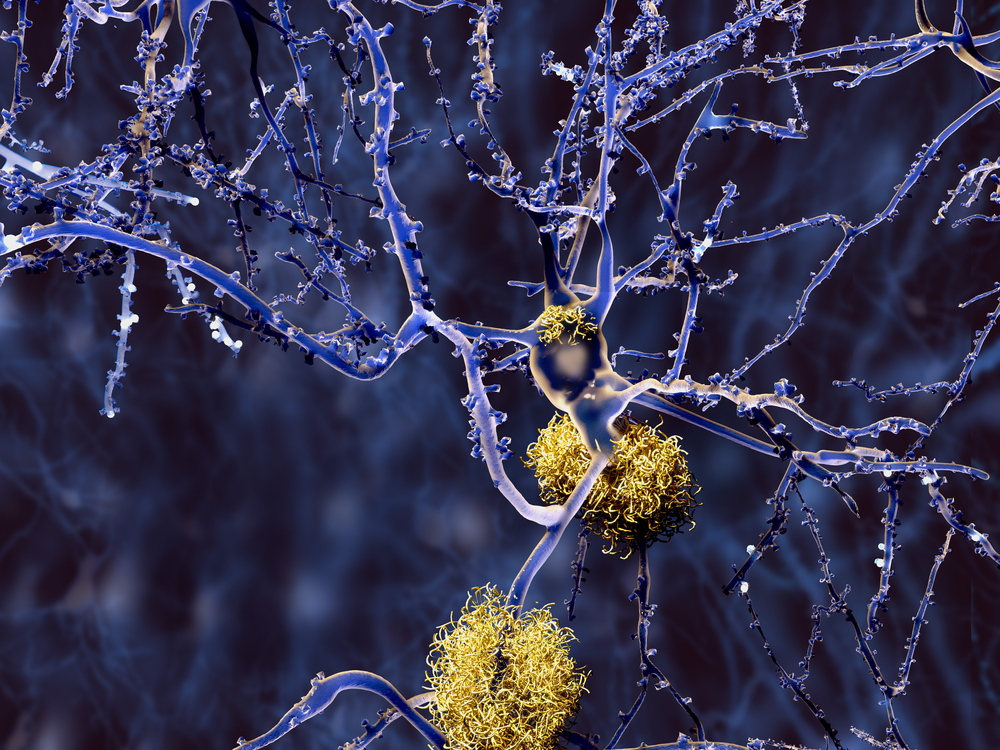

Researchers have found that amyloid, the protein that forms toxic aggregates, or clumps in the brain and is thought to be involved in the onset of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), accumulates faster in people with subtle cognitive difficulties compared with cognitively normal people.

These findings suggest that measurements of mild cognitive impairment may be a sensitive and noninvasive predictor of neurodegeneration.

The study, “Objective subtle cognitive difficulties predict amyloid accumulation and neurodegeneration,” was published in Neurology.

Amyloid accumulation is a key characteristic of Alzheimer’s and is associated with the cognitive decline and neurodegeneration observed in this patient population. However, it is not well understood how early in the disease amyloid starts to build up and how much it accounts for Alzheimer’s symptoms.

Generally, Alzheimer’s disease gradually progresses in stages characterized by the increase of amyloid plaques in the brain and eventually nerve cell death.

It is possible to identify early stages of Alzheimer’s before severe symptoms of the disease and amyloid plaques are present. This can be done using neuropsychological (behavior) assessments that test learning and memory.

A set of “objectively-defined subtle cognitive difficulties,” termed Obj-SCD, has been identified in previous research and can be used to classify patients during the early stages of Alzheimer’s.

People classified as having Obj-SCD may have overall assessment scores in the normal range but the way in which they complete the tasks given in testing may have Alzheimer’s-associated errors. For example, when asked to remember a list of words, these individuals can usually recall an average number of correct words. However, they might add some extra words that were not in the original list.

Having Obj-SCD has been shown to predict faster progression to mild cognitive impairment, or MCI, and dementia in comparison with those who do not have Obj-SCD and are classified as cognitively normal. Obj-SCD also has been associated with the presence of biomarkers for Alzheimer’s present in the cerebralspinal fluid (CSF), the liquid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord.

Now, the researchers wanted to understand whether Obj-SCD occurs before or after amyloid starts to accumulate, and whether it can be used to predict future amyloid accumulation and neurodegeneration.

The study included 747 people who did not have dementia who were enrolled in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) — a multicenter study that unites researchers with study data. The initiative, launched in 2003, involves repeated brain imaging, assessment of biomarkers, and clinical measurements to track the progression of MCI and Alzheimer’s.

Among the participants, 305 were cognitively normal, 153 were classified as Obj-SCD, and 289 had MCI. Behavior tests and brain imaging scans, including positron emission tomography (PET) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), were carried out over a four-year period.

“This is the first study, to our knowledge, to investigate the relationship between Obj-SCD, defined using sensitive neuropsychological measures, and the trajectory of amyloid PET changes,” the researchers said.

The team found that amyloid accumulation was faster in participants classified as having Obj-SCD than in the cognitively normal group. Additionally, it was shown that Obj-SCD can be identified before or at the same time as the early phase of amyloid accumulation.

The cognitive difficulties also could predict the progression to MCI and dementia. “The Obj-SCD group had nearly 3 times the proportion of [participants] who are later classified as MCI (46.0%) at 48 months compared to CN [cognitively normal] participants (16.9%),” the researchers said.

Participants with Obj-SCD and MCI had faster thinning, over 48 months, of the entorhinal cortex — a part of the brain affected in the early stages of Alzheimer’s which is associated with memory, navigation and perception of time — compared with cognitively normal individuals.

However, the results showed that participants with MCI had a faster rate of entorhinal cortex thinning than did those with Obj-SCD. These participants also exhibited faster atrophy of a brain region known as the hippocampus that’s involved in learning and memory.

“The scientific community has long thought that amyloid drives the neurodegeneration and cognitive impairment associated with Alzheimer’s disease,” Mark W. Bondi, PhD, professor of psychiatry at the UC San Diego School of Medicine and the VA San Diego Healthcare System, and the study’s senior author, said in a press release.

“These findings, in addition to other work in our lab, suggest that this is likely not the case for everyone and that sensitive neuropsychological measurement strategies capture subtle cognitive changes much earlier in the disease process than previously thought possible,” Bondi said.

“Obj-SCD … can be identified prior to or during the preclinical stage of amyloid deposition,” the researchers said. They said this measurement may be a sensitive and noninvasive predictor of amyloid deposits and neurodegeneration, prior to the cognitive impairment associated with MCI.

“While the emergence of biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease has revolutionized research and our understanding of how the disease progresses, many of these biomarkers continue to be highly expensive, inaccessible for clinical use or not available to those with certain medical conditions,” said Kelsey Thomas, PhD, the study’s first author, an assistant professor of psychiatry at UC San Diego School of Medicine and research health scientist at the VA San Diego Healthcare System.

“A method of identifying individuals at risk for progression to AD using neuropsychological measures has the potential to improve early detection in those who may otherwise not be eligible for more expensive or invasive screening,” Thomas said.