Harmful Tau Protein Shows Up in One Brain Area, Then Spreads, Study Reports

The harmful tau protein associated with Alzheimer’s appears in one place in the brain, then spreads, rather than showing up in several places independently, new imaging techniques show.

This finding suggests that preventing tau from spreading may be a good way of stopping the progression of the disease, a University of Cambridge research team said. Tau kills nerve cells and damages their connections.

Another finding was that tau build-ups damage the wiring in the brain, leading to fewer connections between nerve cells. This may underlie the confusion and fading of memories in Alzheimer’s patients, researchers said.

The study, “Tau burden and the functional connectome in Alzheimer’s disease and progressive supranuclear palsy,” appeared in the journal Brain.

Tau is one of two proteins whose build-up in nerve cells drives the progression of Alzheimer’s. The other is amyloid beta and tau.

Scientists believe amyloid beta accumulates first, paving the way for the accumulation and spread of tau. Tau is responsible for the most detrimental symptoms of Alzheimer’s — cognition and memory loss.

Researchers have used mouse models that mimic Alzheimer’s to understand the mechanisms of the disease. But until now, researchers have been able to study its mechanisms in humans only by examining the brain tissue of people who died.

New developments in positron emission tomography scanning are finally allowing researchers to look at tau in the brains of living patients. Injecting patients with a radioactive ligand that binds to tau makes the protein visible in a PET scanner.

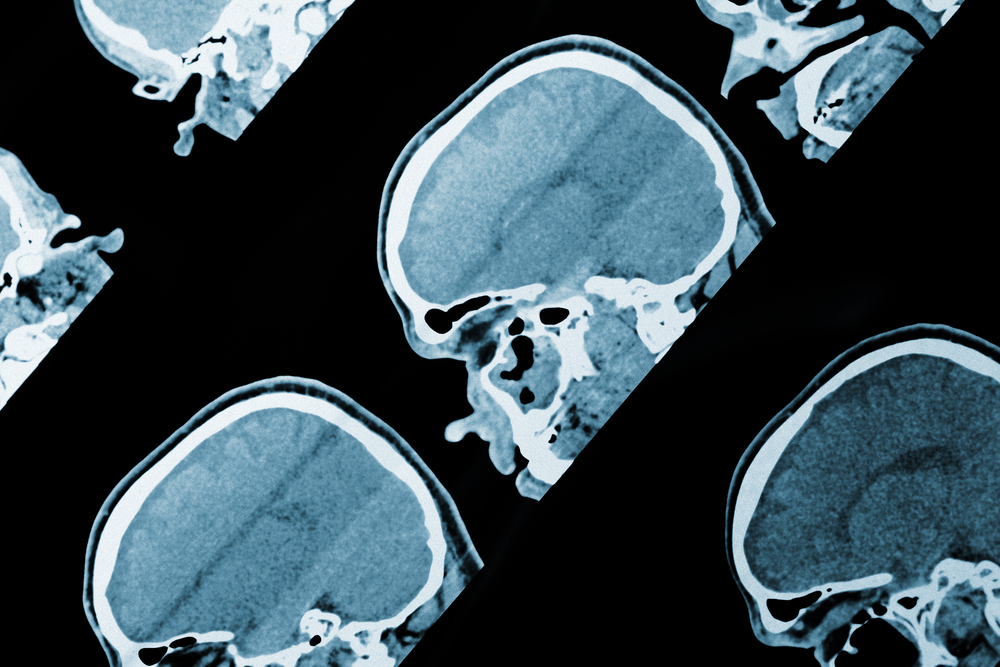

The Cambridge scientists used a combination of PET imaging and magnetic resonance imaging to examine how tau affected the wiring in the brains of 17 Alzheimer’s patients.

An important part of the study was using the new imaging setup to answer the question of how tau appears in the brain. Scientists have offered three hypotheses.

One, known as transneuronal spread, is that abnormal tau spreads as a chain reaction. Proponents of this scenario have posited that tau first accumulates in a specific place, then spreads.

Another hypothesis is called metabolic vulnerability. Its proponents argue that tau is made locally in nerve cells. But some brain regions have higher energy-conversion demands, making them more vulnerable to the protein, proponents say.

Scientists call the other hypothesis trophic support. It also suggests that certain brain regions are more vulnerable to tau build-up. But the accumulation is caused by lack of nutrition rather than higher metabolic demand, proponents contend.

The new scanning breakthroughs allowed the Cambridge researchers to test the three hypotheses.

“Five years ago, this type of study would not have been possible, but thanks to recent advances in imaging, we can test which of these hypotheses best agrees with what we observe,” Dr. Thomas Cope of Cambridge’s Department of Clinical Neurosciences, said in a press release. He was the study’s first author.

By looking at the link between tau and the wiring in Alzheimer’s patients’ brains, researchers found evidence supporting the transneuronal spread hypothesis — the one arguing that the protein accumulates in one place, then spreads.

“If the idea of transneuronal spread is correct, then the areas of the brain that are most highly connected should have the largest build-up of tau and will pass it on to their connections,” Cope said. “It’s the same as we might see in a flu epidemic, for example. The people with the largest networks are most likely to catch flu and then to pass it on to others. And this is exactly what we saw.”

“In Alzheimer’s disease, the most common brain region for tau to first appear is the entorhinal cortex area, which is next to the hippocampus, the memory region,” said Professor James Rowe, the study’s lead author. “This is why the earliest symptoms in Alzheimer’s tend to be memory problems. But our study suggests that tau then spreads across the brain, infecting and destroying nerve cells as it goes, causing the patient’s symptoms to get progressively worse.”

The findings suggest that therapies that preventing tau from spreading to other nerve cells may slow or even stop the progression of Alzheimer’s.