In Alzheimer’s Disease, Adaptive Immune System Plays Important Role

Written by |

Researchers have discovered that a genetic elimination of peripheral immune cell populations leads to a more rapid development of amyloid brain plaques (which are present in Alzheimer’s patients), worsening of neuroinflammation, and dysfunction of microglial activity.

The study, “The adaptive immune system restrains Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis by modulating microglial function,” was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

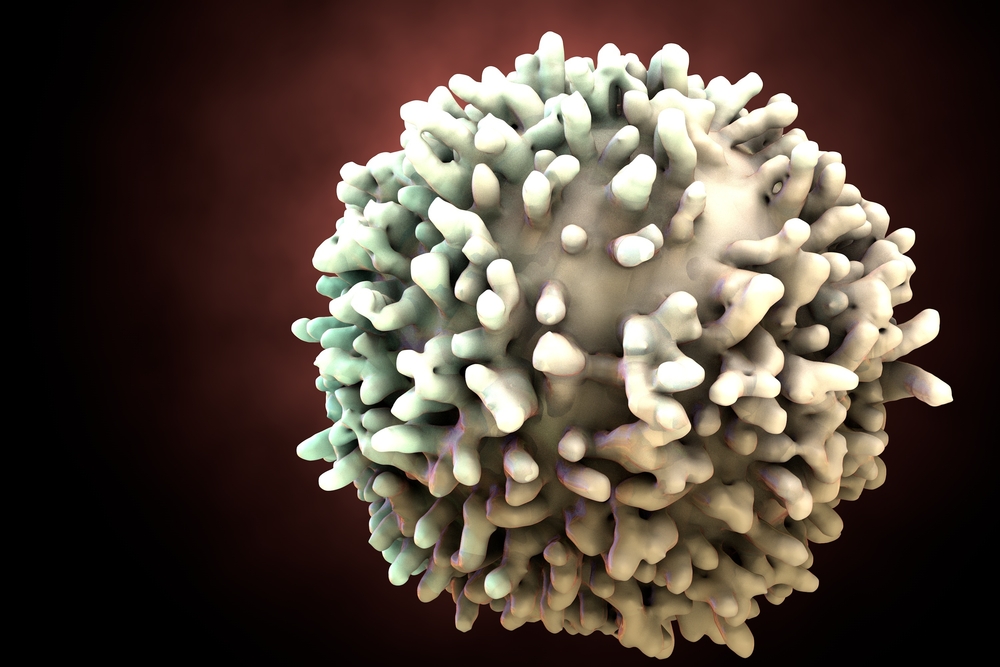

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the leading cause of age-related neurodegeneration, is characterized by two protein aggregate structures, amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. Usually, microglia — immune system cells that act in the central nervous system — respond and destroy these plaques, but eventually develop a more pro-inflammatory role and contribute to the chronic neuroinflammation observed in Alzheimer’s disease.

Research has long focused on and uncovered the role of innate immunity in Alzheimer’s development, but the adaptive immune system’s role remains largely unknown. The number of clinical trials studying vaccination strategies for Alzheimer’s indicates that the adaptive immunity may indeed be a significant player in Alzheimer’s.

To investigate if the adaptive immune system, specifically immune B- and T-cells, plays a role in Alzheimer’s pathogenesis, researchers developed a genetically modified mouse model of AD that lacked T, B, and natural killer (NK) cells. The researchers observed that these mice had a twofold increase in amyloid plaque accumulation when compared to normal mice. Gene expression analyses indicated altered innate and adaptive immune pathways, with changes in cytokine and chemokine signaling and antibody-mediated processes.

Neuroinflammation was found to be greatly increased and microglia exhibited a less phagocytic phenotype and more pro-inflammatory profile. Bone marrow transplantation into mutant mice led to the regeneration of these missing cell populations and greatly reduced amyloid plaques. Researchers found that losing such cells increased amyloid plaques due to the loss of antibodies (produced by B-cells), which in a normal situation can associate with microglia and help clearance of these plaques.

“We know that the immune system changes with age and becomes less capable of making T- and B-cells,” senior author Mathew Blurton-Jones, assistant professor of neurobiology and behavior, said in a press release. “So whether aging of the immune system in humans might contribute to the development of Alzheimer’s is the next big question we want to ask.”