Diet Directly Affects Gut Bacteria and May Contribute to Alzheimer’s Progression, Pilot Study Suggests

Written by |

A modified Mediterranean-ketogenic diet can regulate bacteria in the gut that may contribute to the development and progression of cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease, results from a pilot study suggest.

Those findings come from a small study by researchers at Wake Forest School of Medicine, which was published in The Lancet journal EBioMedicine.

“The relationship of the gut microbiome and diet to neurodegenerative diseases has recently received considerable attention,” Hariom Yadav, PhD, said in a press release. Yadav is an assistant professor at Wake Forest School of Medicine and co-author of the study. “Our findings provide important information that future interventional and clinical studies can be based on.”

The study was titled “Modified Mediterranean-ketogenic diet modulates gut microbiome and short-chain fatty acids in association with Alzheimer’s disease markers in subjects with mild cognitive impairment.”

Alzheimer’s is characterized by the formation of plaques, or clumps, of a toxic version of amyloid-beta molecules within nerve cells. This leads to the activation of immune cells resident in the brain, known as microglia, which can help remove these amyloid plaques. However, if overactivated, microglia can trigger neuroinflammation (inflammation of the central nervous system.

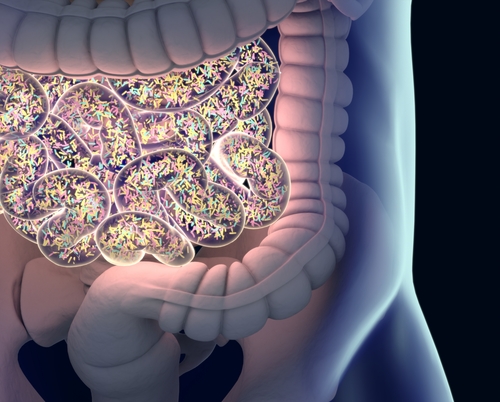

Several factors can influence neuroinflammation, including the bacteria that reside in the intestines, which are collectively named the gut microbiome.

Prior studies have found that people with cognitive impairment have altered gut microbiota. This is associated with an increase in the levels of pro-inflammatory molecules in the blood and progression of neuroinflammation.

Although it is not fully understood how gut microbiome may affect Alzheimer’s progression, it is widely acknowledged that dietary patterns may play a role.

Western diets, which often are rich in saturated fats and simple carbohydrates, have been associated with increased risk of Alzheimer’s. In contrast, other dietary patterns with high mono- and poly-unsaturated fats, vegetables, fruits, and lean proteins, are associated with reduced Alzheimer’s risk.

This evidence suggests that a Mediterranean-style diet is not only “a prudent lifestyle choice but also as a scientifically accepted mechanism able to confer benefits for prevention and management” of diseases and overall well-being, researchers said.

Wake Forest researchers now explored the impact of the so-called Mediterranean diet in the gut microbiome and the overall risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

The study (NCT02984540) enrolled 17 participants, of whom 11 had mild cognitive impairment and six had no cognitive problems. They were divided randomly into two groups to receive a modified Mediterranean diet or the American Heart Association Diet (AHAD) for six weeks. At the end of that period they stopped taking the dietary intervention for six weeks, after which they started the other diet for an additional six weeks.

The modified Mediterranean diet consisted of low-carbohydrate daily intake (less than 20 grams of carbohydrates per day), and consuming foods with high levels of healthy fats (preferably low in saturated fats). Carbohydrates were expected to make up less than 10% of total caloric intake.

The AHAD consisted of a low-fat, higher-carbohydrate meal plan. Participants were encouraged to limit the amount of fat intake to less than 40 grams per day, while eating plentiful fruits and vegetables. Carbohydrates were expected to make up 50–60% of total caloric intake.

Initial analysis of bacteria diversity in fecal matter of all participants did not show significant differences between those with or without cognitive impairment. Still, people with cognitive impairment showed a unique microbial pattern. The team also noted that the presence of particular bacteria was associated with levels of recognized biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease.

After completion of the six-week dietary intervention no major changes were reported on the overall microbiome diversity between the two groups, regardless of the diet. Still, the different dietary patterns led to some significant changes at the specific pattern of gut microbiome, with some bacteria family being reduced or increased with either the modified Mediterranean diet or the AHAD.

Importantly, the bacterial changes induced by the modified Mediterranean diet were linked reduced levels of Alzheimer’s biomarkers, such as tau protein and beta-amyloid molecules.

“Our results encouragingly suggest that specific gut microbiome signatures and organic acids might be used as biomarkers for” Alzheimer’s and like diseases, they concluded.

“Determining the specific role these gut microbiome signatures have in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease could lead to novel nutritional and therapeutic approaches that would be effective against the disease,” Yadav said.