FDG PET Scan More Accurately Assesses Severity of Cognitive Decline in Alzheimer’s, Study Finds

Written by |

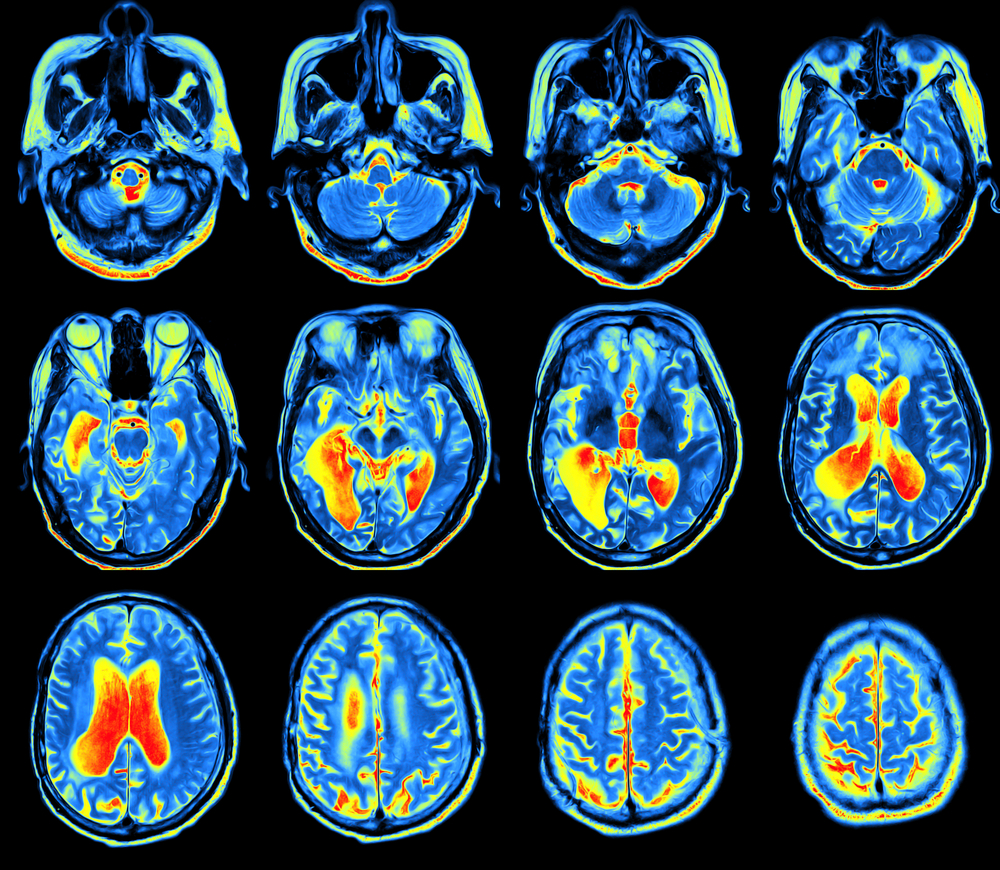

Compared to regular amyloid imaging, fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET), an imaging technique that quantifies brain function by measuring glucose levels, can better assess the progression and severity of cognitive decline in people with Alzheimer’s, and also cognitive impairment, researchers have found.

Their study, “18F-FDG Is a Superior Indicator of Cognitive Performance Compared to 18F-Florbetapir in Alzheimer’s Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment Evaluation: A Global Quantitative Analysis,” was published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Progressive decline in cognitive function is the primary clinical manifestation in Alzheimer’s, whose disease mechanism is widely believed to be driven by the production and deposition of a protein called amyloid-beta.

“Two of the most significant biomarkers found in [Alzheimer’s disease] are decreased cortical [relating to the brain’s outer layer] glucose metabolism and the accumulation of [amyloid-beta] plaques, both of which can be measured using current imaging techniques with positron emission tomography (PET),” the researchers wrote.

The 18F-florbetapir PET scan detects amyloid plaques in the brain, which are the prime suspects in damaging and killing nerve cells in Alzheimer’s. Before the existence of amyloid imaging, these harmful aggregates could be detected only after a patient’s death.

However, imaging studies indicate the presence of amyloid-beta is necessary, but not sufficient, for manifestations of the neurodegenerative disorder or even cognitive decline. In fact, scientists have observed high levels of amyloid-beta in non-demented individuals. So, there is a need to explore the potential of other imaging techniques in assessing Alzheimer’s-related cognitive decline.

Investigators compared the effectiveness of 18F-FDG PET and 18F-florbetapir PET in evaluating the cognitive performance of people with Alzheimer’s, those with mild cognitive impairment, and a group of healthy people used as controls. Both imaging techniques are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

18F-florbetapir PET assesses amyloid load while 18F-FDG PET detects changes in brain glucose metabolism — one of the brain’s main sources of energy.

Sixty-three individuals (36 men and 27 women; average age 68.3 years) were enrolled in the study. Of those, 19 had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, 23 had mild cognitive impairment, and 21 were healthy.

All subjects underwent 18F-FDG and 18F-florbetapir PET imaging, and cognitive function examination through the application of the Mini Mental State Exam. To perform their analyses, researchers focused on five brain regions: supra-tentorial (the brain excluding the cerebellum), cerebellar (referring to the cerebellum), frontal (front part of the brain), parieto-occipital (back top half of the cerebrum), and temporal (referring to the area that sits behind the ears, that is responsible for memory storage, visual recognition of faces and objects, and the use of language).

Both 18F-FDG and 18F-florbetapir successfully detected individuals with dementia. However, 18F-FDG findings correlated significantly with cognitive tests’ results.

The correlation of 18F-FDG with the Mini Mental State Exam was stronger than that of the 18F-florbetapir PET in two of the analyzed regions: supra-tentorial and temporal.

Importantly, the association between low cognitive performance and high levels of amyloid was significantly weaker than the one between 18F-FDG and low cognitive performance across all study subjects, indicating 18F-FDG can detect cognitive decline more accurately.

“Our results support the notion that amyloid imaging does not reflect levels of brain function, and therefore it may be of limited value for assessing patients with cognitive decline,” Abass Alavi, MD, PhD, a professor of Radiology at the University of Pennsylvania, and the study’s co-principal investigator, said in a press release.

The discovery enables doctors to optimize and increase the accuracy of their diagnoses. “In a clinical drug trial, for example, it may be more relevant to do an FDG-PET scan, rather than using amyloid as a marker, to find out whether the therapy is working,” said Andrew Newberg, MD, a professor of Radiology at Thomas Jefferson University, and the study’s co-lead author.

“Right now, FDG is king when it comes to looking at brain function, not only in Alzheimer’s disease, but also diseases like vascular dementia and cancer,” Alavi said.