Lack of Awareness of Memory Problems Seen as Sign of Alzheimer’s Risk in Study

Written by |

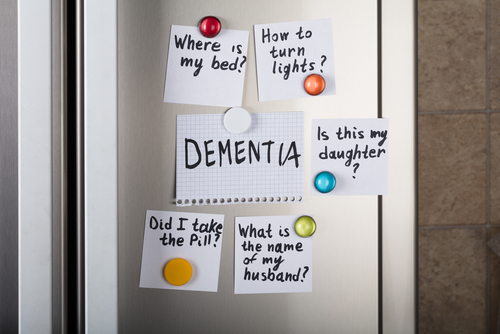

A person’s awareness of a cognitive problem, such as memory loss, may be a good indication that he or she is not going to develop Alzheimer’s disease.

According to a study conducted by researchers at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) in Toronto, Canada, people who are unaware of an increasingly evident decline in memory — and other symptoms of cognitive decline or mental illness, a condition medically known as anosognosia — are more likely to develop the disease.

This finding was reported in the study “Anosognosia Is an Independent Predictor of Conversion From Mild Cognitive Impairment to Alzheimer’s Disease and Is Associated With Reduced Brain Metabolism” that appeared in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

“If patients complain of memory problems, but their partner or caregiver isn’t overly concerned, it’s likely that the memory loss is due to other factors, possibly depression or anxiety,” Dr. Philip Gerretsen, clinician scientist at CAMH and a study lead author, said in a news release. “They can be reassured that they are unlikely to develop dementia, and the other causes of memory loss should be addressed.”

The study included 1,062 participants, ages 55 to 90, with the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). Of that total, 191 people were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, 499 had mild cognitive impairment, and 372 were healthy volunteers.

Brain cells, to work well, need to consume a sugar called glucose. Both with Alzheimer’s and in memory loss, however, glucose uptake is impaired. Using positron emission tomography (PET) imaging scans, the researchers could detect glucose consumption by brain cells, and identify which parts of the brain were affected in patients with anosognosia.

They observed that low glucose uptake was associated with anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease patients. In addition, they found that patients unaware of their memory loss problems were 2.74 times more likely to develop Alzheimer’s within five years.

“The absence of anosognosia may be clinically useful to identify those patients that are unlikely to convert from MCI [mild cognitive impairment] to AD [Alzheimer’s disease],” the researchers concluded.

To follow-through these findings, Dr. Gerretsen and his team are planning to evaluate the impact of therapeutic interventions on illness awareness and ways to prevent of mild cognitive impairment from progressing to dementia. This new study will be integrated in the ongoing PACt-MD trial (NCT02386670), and is now recruiting adults, ages 60 and older, with either mild cognitive impairment or major depressive disorder (in remission) at about a half-dozen sites across Canada.