Low Serotonin in Brain May Explain Cognitive Impairment, Johns Hopkins Study Shows

Written by |

Johns Hopkins researchers looked at brain scans and discovered that lower levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin underlie the mild loss of cognitive functions that usually precede the onset of Alzheimer’s disease.

These findings suggest that preventing the loss of serotonin could halt or even prevent the progression of Alzheimer’s disease and potentially other dementias.

The study, “Molecular imaging of serotonin degeneration in mild cognitive impairment,” was published in the journal Neurobiology of Disease.

“Now that we have more evidence that serotonin is a chemical that appears affected early in cognitive decline, we suspect that increasing serotonin function in the brain could prevent memory loss from getting worse and slow disease progression,” Gwenn Smith, PhD, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and study first author, said in a press release.

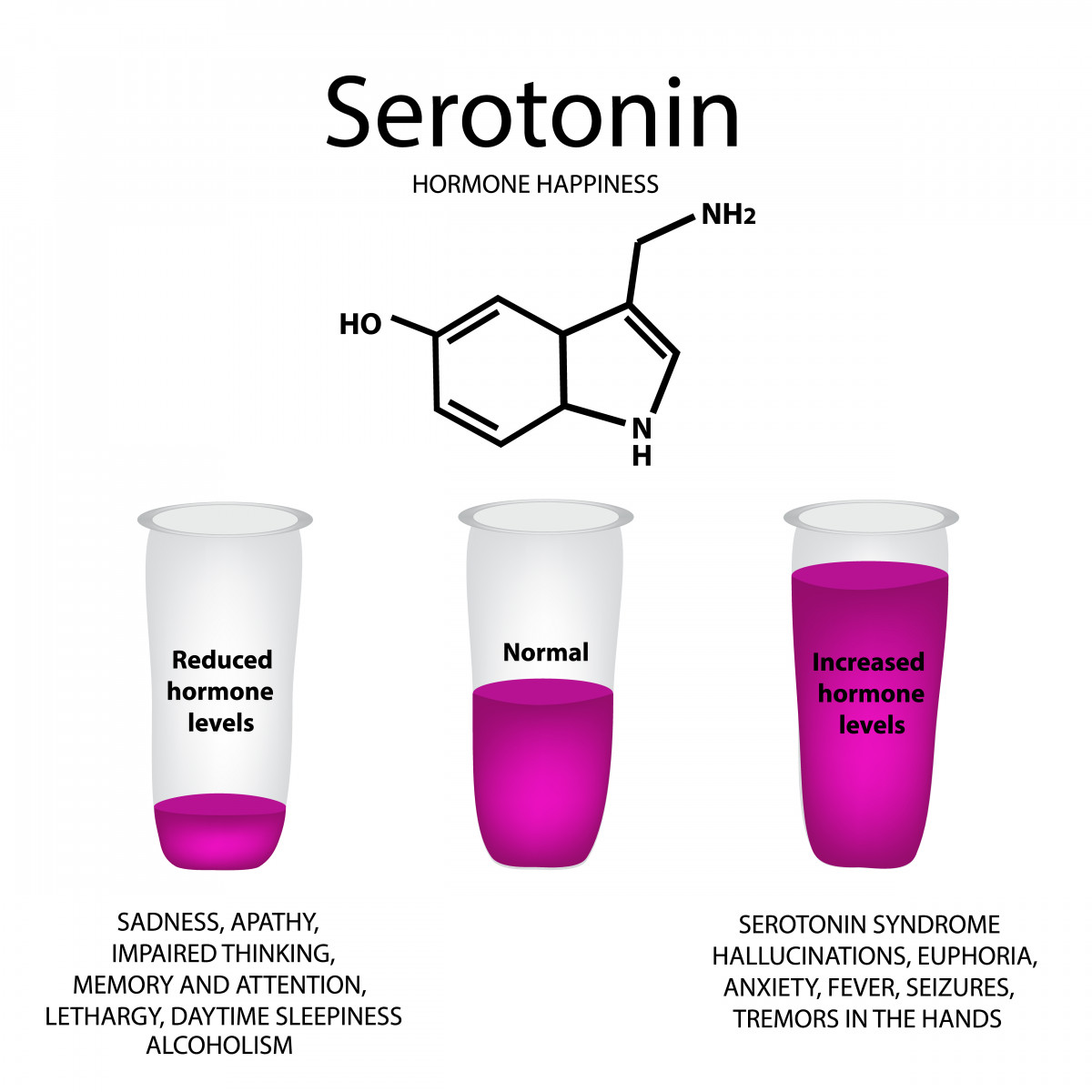

Serotonin is an important neurotransmitter that controls many functions within our body, including mood, sleep, and appetite. Marked loss of serotonin nerve cells (or neurons) is a phenomenon that characterizes diseases associated with a severe cognitive decline, including Alzheimer’s. Until now, it remained unknown whether decreased levels of serotonin were a cause of cognitive impairment or a consequence of it.

To address this question, the Johns Hopkins researchers analyzed live images of brains, obtained by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and tracked serotonin levels in the brains of the study participants using positron emission tomography (PET). The study recruited 28 individuals with mild cognitive impairment, a phenotype that may indicate a future risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease or other dementias, and an equal number of healthy, cognitively normal, matched controls.

Mild cognitive impairment was defined as a small decrease in cognitive abilities, mainly in terms of memory, when patients had problems remembering sequences, and difficulties with organization. Additionally, these patients also scored low in the California Verbal Learning Test, where participants are required to remember a list of related words, such as a shopping list. This simple test actually reflects participants’ changes in memory and cognitive impairment.

The analysis showed that those with mild cognitive impairment had a deficit of serotonin levels in their brains, up to 38 percent less, when compared to age-matched healthy controls. Moreover, lower serotonin was associated with worse performance in both verbal and visual-spatial memory tests.

For example, in the California verbal learning test, with a scale that goes from 0 to 80, while healthy controls scored an average of 55.8, those with mild cognitive impairment scored an average of 40.5. In the brief visuospatial memory test, where patients were required to memorize a series of shapes so that they could reproduce it later, the results showed the same tendency: In a test where scores range from 0 to 36, healthy participants scored an average of 20.0, while those with mild cognitive problems scored an average of 12.6.

Smith’s team is now investigating whether assessing the levels of serotonin using PET imaging may be a useful strategy to detect disease progression in Alzheimer’s disease patients. The imaging could be performed alone or combined with other techniques that assess the level of amyloid deposits, the other protein implicated in the disease.

These findings also suggest that targeting serotonin is a potential therapeutic strategy, although Smith said that targeting the receptors for serotonin is actually the better approach, since there are 14 of those. Moreover, drugs targeting these receptors are under investigation in several clinical trials.