Vaccine Seen to Lessen Signs of Neurodegeneration in Phase 2 Trial

Written by |

Den Rise/Shutterstock

AADvac1, an investigational vaccine targeting abnormal tau protein, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease, was found to be safe and effectively reduced the signs of neurodegeneration in patients with mild disease, according to data from the ADAMANT Phase 2 clinical trial.

In a subgroup of participants with a confirmed Alzheimer’s biomarker profile, AADvac1 significantly slowed clinical and functional decline, the scientists noted.

“The recent approval of an amyloid-based therapy [Aduhelm] was encouraging for the whole Alzheimer’s industry,” Norbert Zilka, PhD, of Axon Neuroscience, the therapy’s developer, said in a press release.

“Unlike amyloid, which influences speed of Alzheimer’s progression, there is strong evidence that tau pathology relates to the underlying cause of the disease,” Zilka said. “Our vaccine aims to halt the formation and spread of tau pathology, which has ultimately the potential to show a higher benefit for Alzheimer’s disease patients.”

The study, “ADAMANT: a placebo-controlled randomized phase 2 study of AADvac1, an active immunotherapy against pathological tau in Alzheimer’s disease,” was published in the journal Nature Aging.

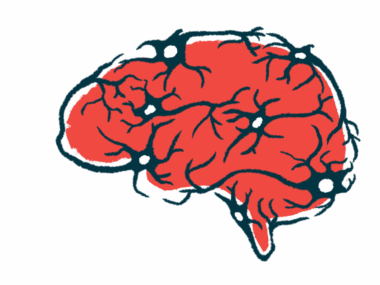

The hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease are amyloid-beta deposits and the accumulation of aberrant forms of tau protein in the brain. Tangles of tau protein are associated with the loss of nerve cells (neurons), brain shrinkage (atrophy), cognitive impairment, and dementia severity.

AADvac1 is a vaccine designed to induce the immune system to generate antibodies that target and clear abnormal forms of tau, and ultimately to protect neurons from degeneration.

In animal models, AADvac1 reduced tau tangles and improved disease-related characteristics. Early human trials demonstrated the vaccine safely elicited high levels of antibodies and resulted in signs of improved cognitive impairment.

Based on these findings, AADvac1 was advanced into the now complete ADAMANT Phase 2 clinical trial (NCT02579252), reported in detail in the recently published study by scientists based at Axon, the trial’s sponsor.

ADAMANT was a 24-month (two-year) trial that enrolled 196 people with mild Alzheimer’s in eight countries across Europe. The participants were randomly assigned: 117 to AADvac1 and 79 to a placebo vaccine. Patients received six doses at four-week intervals, then five additional booster doses three months apart.

The trial met its primary goal of safety, with no differences in adverse side effects between the ADDvac1-treated and placebo groups.

Secondary goals included the vaccine’s ability to generate antibodies (immunogenicity) as well as its effectiveness on clinical outcomes and other disease biomarkers. A complete analysis was conducted with 193 participants who had at least one efficacy assessment. In the end, 163 participants completed the trial by attending a clinical visit after two years (104 weeks).

Treatment-related serious adverse events (SEAs) were seen in 17.1% of those treated with AADvac1 and in 24.1% of placebo participants. Injection-site reactions were the only reported adverse event (AE) that occurred significantly more often in AADvac1-treated individuals.

The incidence of confusion was significantly higher in AADvac1-treated patients than placebo patients (5.1% vs. 0%), but this AE was not long-lasting and resolved in five of the six who experienced confusion.

“The observed AEs and SAEs were in line with the background incidence expected in the elderly [Alzheimer’s disease] population; no safety signal emerged,” the team wrote.

Two patients on active treatment died, but their deaths were not considered related to AADvac1 by investigators and the trial’s Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) — a group of independent medical experts that monitored patient safety during the trial.

No statistically significant differences were seen in vital signs, and blood and urine tests between the treatment and placebo groups. MRI scans also showed no differences in blood vessel swelling or incidence of small brain hemorrhages.

“The independent DSMB concluded in its final report that no significant safety concerns that would prevent the continued development of AADvac1 were identified in the ADAMANT trial,” the team added.

AADvac1 induced a robust immune response after six doses, with 98.3% of patients overall generating antibodies against abnormal tau. Boosters — extra doses of the vaccine that help develop a strong immune response — effectively maintained this response. These data were consistent with findings from a previous Phase 1 study (NCT01850238).

Clinical outcome measures were assessed by the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB) — a scale to measure dementia severity among the patient population. A comparison of 100 AADvac1-treated patients with 63 placebo-treated individuals after two years found no statistically significant differences.

“In summary, neither positive nor negative effects of AADvac1 treatment on cognition and function were detectable in this sample,” the scientists wrote.

AADvac1 significantly reduced the buildup of the neurofilament light chain (Nfl), a biomarker reflecting ongoing neurodegeneration and the development of dementia. Before treatment, the levels of Nfl were the same between the treatment and placebo groups. After two years, mean Nfl increased by 12.6% in the AADvac1-treatment group compared to 27.7% in the placebo group.

Further analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which surrounds the brain and spinal cord, also showed significant reductions in disease-related tau, including the specific CSF biomarker phosphotau–T217. The impact of the vaccine on amyloid-beta in the CSF was minor.

Based on MRI scans, no meaningful difference in brain atrophy was observed between AADvac1-treated and placebo-treated groups after two years. Also, by MRI, fractional anisotropy and mean diffusivity were evaluated to measure the integrity of brain white matter. Reduced fractional anisotropy and increased mean diffusivity reflect neurodegenerative processes. Compared to placebo, the vaccine stabilized these measures in the fornix area of the brain, a white matter tract that is important in Alzheimer’s.

Finally, as most patients were enrolled based solely on MRI scans, a substantial portion of participants did not fulfill the Alzheimer’s diagnostic criteria based on CSF biomarkers, which included measurements of CSF tau, phosphotau–T217, and amyloid-beta.

In a subgroup analysis of those that did fulfill these criteria, compared to placebo, the AADvac1 vaccine significantly slowed clinical decline by 27%, as measured by CDR-SB, and reduced functional decline by 30%, as assessed by the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-mild cognitive impairment-Activities of Daily Living. These improvements were mirrored by a 62% reduction in Nfl levels. Brain atrophy measurements were inconclusive in this analysis.

“Together, the preclinical and clinical data support further development of AADvac1,” the authors wrote. “Adequately powered phase 3 studies will be required to attempt to replicate biomarker effects on larger sample sizes and to draw robust conclusions about clinical efficacy of AADvac1.”